Our planet is rapidly growing warmer. Initiatives are surfacing to not just adapt to, but actively combat the accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Carbon capture technology is in its infancy, but we already have one method of removing CO2 from the atmosphere – trees.

Apart from the multitude of other benefits they bring to the land around them, trees are great at literally drawing CO2 from the air and into their own biomass and then into the soil, a process known as carbon sequestration.

Danish foresters have begun promoting the idea of using wood to replace energy intensive construction materials, such as concrete. Sustainable forestry would mean to not only increase the global forest cover, but to use wood for its most efficient purpose and thus keep CO2 locked within it for longer. From this perspective, it is all the more tragic that Uganda’s total forest cover has shrunk by 90% from 1990 to 2015 and continues to be in peril.

Deforestation in Uganda – a human issue

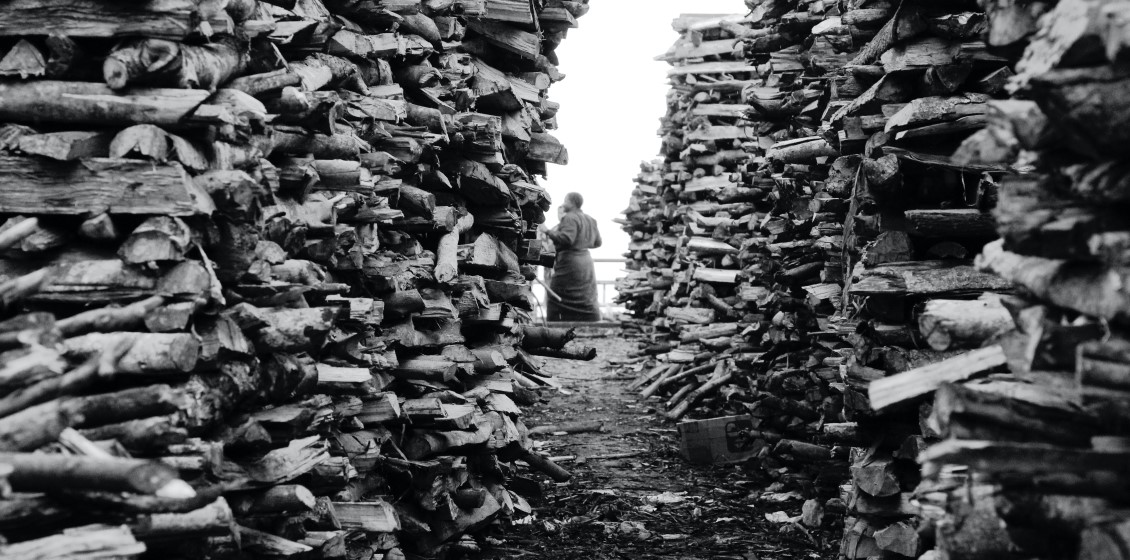

Uganda’s forest loss is a tragedy on multiple levels. Like deforestation elsewhere, the main driver is human activity. In Uganda, forests are cut down to be used as an energy source, and to increase available land for subsistence farming. The growing construction sector also demands more wood. A shrinking forest means a shrinking basis for existence for the ever-increasing population in Uganda.

Apart from its human cost, the tropical forest is home to the majority of our landbound animal species. The same is not true of European forests: The wealth of life on land in the tropical regions is unmatched. Preserving the remaining forest is a domestic challenge for Uganda, but climate change mitigation is a global effort. A greater forest cover in Uganda is a boon to us all, non-humans included.

The people of Uganda benefit directly from the forest in many ways, but notably as a cheap energy source. Forests provide a mixture of charcoal and fuelwood. Using wood as fuel is its least sustainable function and should be the last step in a cascade of wood usage in a circular economy. At the top of the cascading stairs is the longest-lasting use of wood, with the final step being conversion to energy.

However, most Ugandans have little choice. Electric power is presently too unstable and too expensive to be a legitimate alternative to charcoal. Charcoal making and subsistence farming are many peoples livelihood. To solve Uganda’s problem with deforestation, several social and economic issues must be addressed first. No matter how many tree planting initiatives are set in motion or supported by various institutions and NGOs, trees are disappearing much faster than they can be regrown.

Outsourcing the problem

The management of forests in Uganda does not fall within the purview of the European Commission (EC). With their new forest strategy, the EC emphasizes a circular economy where wood is sourced sustainably yet wishes to expand protected forest areas within the EU. They also acknowledge in the same document that “forest-related challenges are inherently global”.

If the chosen method to mitigate climate change is to expand forest cover, the EU (and other Global North actors) should ensure that part of their strategy involves supporting the planting and management of forests outside of their borders. It is also important to find ways to ensure that Global North businesses do not continue to contribute to deforestation in other countries and will monitor wood to make sure it is sourced sustainably.

Private companies have been criticized for taking advantage of afforestation programs and carbon forestry to make themselves seem more environmentally friendly, while having a negative impact on the local area. In carbon forestry, it does not matter which tree species are selected. Fast-growing, and frequently exotic, species are preferred over endemic trees for their quicker turnover.

While monocultures of exotic trees may be beneficial to the general logging industry, they do not improve conditions for wildlife in the area. Furthermore, the foreign owned companies responsible for these plantations have been accused of preventing local access to the area – sometimes violently. These plantations thus serve little other purpose than to ease corporate consciences, while the forested areas still accessible to Ugandans continues to shrink.

Carbon forestry projects have also been criticized for criminalizing the access to forest that the local population is used to and depend on for their livelihoods. Industrial plantations must be part of the plan to increase wood use, but in the meantime, we cannot outsource our climate change mitigation to already vulnerable areas under the pretense of wanting to plant trees. If the EU succeeds in becoming carbon neutral at the expense of the Global South, nothing has been won.

Marrying biodiversity concerns with sustainable forestry

If indeed the ultimate goal is to use more wood and wood products to replace materials that cause greater greenhouse gas emissions, we must also face the fact that not all new forest should be protected. In their 2019 book, ‘Klimaskoven’ (‘The Climate Forest’), Madsen, Nielsen, Madsen and Hilbert suggest that the idea that forests planted for industry are inherently biodiversity deserts does not have to be reality. Instead of planting large swaths of a single species and cut everything down at once, plantations should contain multiple species of different growth rates – what they refer to as mosaic forests. They do acknowledge that this is more labor intensive. However, one of the goals in the ‘New EU Forest Strategy for 2030’ is to create a bigger forestry sector. This more labor-intensive approach could be a solution for the EU’s dual wish to increase both their use of wood as well as improve the biodiversity in forests.

Madsen et al. are not against leaving forested areas untouched for the sake of biodiversity – however, it must be done where it makes the most sense. Where the land is suitable for industrial plantations, there should be sustainably managed plantations. Where it is not, the forest should be left untouched, for example on steep inclines or near exposed water sources. That is how they suggest we ultimately create mosaic forests that can benefit both wildlife and people. Though their research is based on Northern European forests, their ideas for forest management may be applicable around the world, depending on the availability of local expertise.

Exactly because the biodiversity of Uganda is so rich and unique, it is important to choose which areas to protect and which to utilize on a global scale, not just in local mosaics. To help save the forests of Uganda, the Global North must dedicate some effort to helping the country solve its energy crisis and help ensure a stable supply of biomass in the transition period from charcoal to other alternatives. Meanwhile, testing the hypothesis of Madsen et al. in a locale not as dependent on its forests as Uganda could provide more insight on how feasible it is to manage both biodiversity concerns and improve the forestry sector for the benefit of the local economy.

Current limitations

That trees work as carbon sinks is nothing new, but there are some disagreements as to how effective wood is at replacing other materials, particularly in construction. There is also debate on whether old or new forest is more efficient at carbon sequestration. There are currently few clear answers, but there is a benefit to using wood and wood products as a replacement for emissions-intensive material, and we know that forests work as carbon sinks, period.

There is significant uncertainty on just how great a benefit, carbon emissions-wise, it is to substitute concrete and other construction materials for wood. There is also a risk of cross-sector leakage – that is, if concrete becomes cheaper in the Global North because we turn to wood instead, it also becomes more available in the Global South, thus negating any benefit to using wood. Keeping these things in mind, it is understandable if disappointing that the EC delegates the responsibility of getting answers to these questions to the construction and forestry industries.

The Ugandan authorities have multiple initiatives to involve locals in the management of their surrounding forests, albeit with mixed success. One of the main problems in that people are not presented with sufficient or timely enough benefits for them to stop logging and charcoal manufacturing. There is some light at the end of the tunnel, however: Multiple independent businesses have had success with manufacturing charcoal from agricultural waste. Wherever it has been possible to overcome conservative social norms to let women have greater influence on forest management, conservation efforts have seen greater success.

Wrap-up

Forests, especially tropical forests, are referred to as the Earth’s lungs for a very good reason. The immense loss of forest cover in Uganda is an immense issue on multiple levels: Both animal and plant biodiversity suffer, the basis for earning a livelihood for local Ugandans shrinks with every tree felled, and for the rest of the planet, less forest means hotter temperatures and more extreme weather.

Initiatives to address forest loss have tended to use the simple solution and simply plant more trees. But Uganda’s forest cannot recover unless some pervasive economic and social issues are addressed in tandem.

The EU’s strategy to plant 3 billion more trees in Europe by 2030 is an admirable goal, and one to be supported. But even while they openly acknowledge that sustainable forestry should be a global goal, the strategy barely addresses this globality. If we are to achieve sustainable forestry around the world, it is vital and necessary to not just acknowledge, but act on the science that says that not all forests are equal.

Asta Raae is a Master student in International Studies, Faculty of Arts, Aarhus University, DDRN University Intern

SUPPORT DDRN SCIENCE JOURNALISM. DONATE DKK 20 OR MORE APPLICABLE IN DENMARK ONLY

APPLICABLE IN DENMARK ONLY

Esben Møller Madsen, Anders Tærø Nielsen, Palle Madsen, Per Hilbert

Further reading

Leskinen et al. ”Substitution effects of wood-based products in climate change mitigation.” European Forest Institute (2018).

Grassi et al. “Brief on the role of the forest-based bioeconomy in mitigating climate change through carbon storage and material substitution.” European Commission (2021).

Nalule, Victoria R. ed. “Energy Transitions and the Future of the African Energy Sector: Law, Policy and Governance.” Springer International Publishing (2021). ISBN 978-3-030-56849-8.