I have always dreamt of landing a job abroad and that was one of the reasons why I chose to do a master’s in Europe. Given their small population, I had such a notion that it was easier to get absorbed here than in India, where I hail. Perhaps, that was what most of my classmates from the Global South thought before getting to Europe for studies.

Embarking on a European study program had never been easy for young scholars like me from the Global South. For many, it means parting their friends, family, food and above all, their culture. So what is that attracting students to invest thousands of euros in their higher education in Europe? First and foremost is the quality of education with a reputation for excellence and innovation. Second is the exposure that students have to an international job market. Well, this is what most of the educational consultants highlight when they advise students on European universities.

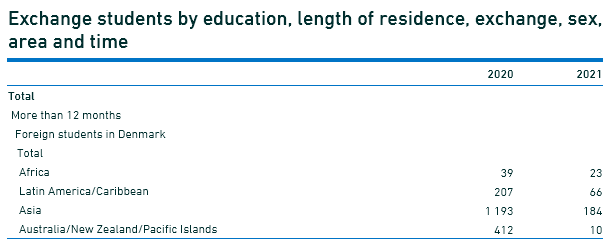

Amongst the Nordic countries, Denmark is one of the most sought-after destinations for higher education. As per the 2022 Times Higher Education World University Rankings, six out of the eight Danish universities are among the top 400 universities in the world. Recent surveys show that Denmark hosts over 30000 international students. If you dig into the 2020 stats, 45% of the international students in Denmark were from Europe, excluding the Nordic countries, 7.5% from the Nordic countries, 7.5 % from Australia/New Zealand/Pacific Islands, 18% from Asia, 14 % from the US/Canada and over 6% from Africa and Latin America put together.

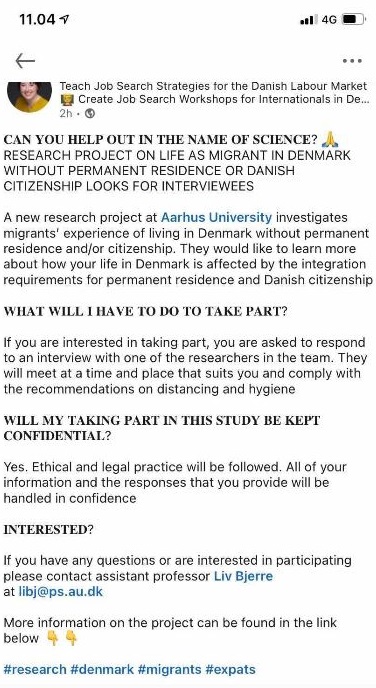

Unlike the Global South students, those from the EU/EEA enjoy free higher education in Danish Universities. This free education elucidates why the share of Global South students in Denmark is low compared to those from Europe. Also, being EU citizens makes it easy for them to establish in Denmark after graduation. Whilst there exist post-study visa schemes to help graduates from non-EU countries to establish in Denmark, it requires them to have relevant jobs related to their discipline. Just having any job wouldn’t help if they want to extend the visa under the establishment scheme. Also, the scheme doesn’t consider freelancers as employed, making it difficult for graduates offering independent consultancies to root themselves in Denmark.

This article discusses the precarious working conditions of international graduates in Denmark. I and two other international graduates will share our experiences with precarity at work and take the readers through our concerns and thoughts on the Danish labour market.

Precarious employment among graduates in Denmark

Precarity is something that people always relate with unskilled labour or other vulnerable groups working in the private sector. Temporary job contracts, changing market-driven labour demands, low wages, risky work conditions and many other insecurities ascribe precarity. Isn’t that prevalent among the graduates as well?

Studies have shown that there exists precarity among young graduates in Denmark. Precarity may be experienced in different forms depending on the graduates’ discipline and the sector in which they work. As a recent graduate, I’m concerned about how international students graduating from Danish Universities experience precarity at work. Given they don’t speak Danish or as beginners, finding a relevant job related to their field of study would be difficult compared to the Danish graduates. Meanwhile, they take up temporary or part-time jobs for a living until they find some relevant positions.

If you look at the unemployment rates in Europe, Denmark is one the countries with minimum unemployment. Thanks to the legislation, labour market organizations, and the collective agreements that regulate the country’s labour market. The Danish labour market follows a ‘flexicurity system’, entitling the employers to hire flexibly and lay off if the situation demands. Whilst it also ensures high social security to employees, protecting them at the time of unemployment.

However, the flexicurity system is becoming more ‘flexi’ now than being secure. This has favoured the employers, compromising the employees’ social security rights under certain conditions of employment. For instance, one’s eligibility for unemployment benefits depends on the hours worked and the employee’s contribution to the unemployment insurance fund. As a consequence, it has become challenging for certain groups such as fixed-term contracts, part-time employees and temporary agency workers to be eligible for unemployment benefits. Also, there is an increasing tendency for employers to hire employees on temporary or short-term contracts, leaving young graduates with concerns on professional development.

As a self-employed courier partner at Wolt, a food delivery company in Denmark, I’m used to exchanging conversations with fellow riders on the way. Not to get surprised, I have met many young graduates from the Global South doing food delivery as they don’t find relevant jobs related to their studies. For many, food delivery is just a transition job until they find something better. While some others from Southern Europe, if I guessed it right, even think of doing it full-time as food delivery is an easy way to make money in Denmark.

I won’t be amazed if the riders continue as full-time courier partners as the job offers flexibility, handsome pay, bonuses, and whatnot. At the same time, there exist some precarity with such jobs. Delivery jobs demand a lot of physical work, especially biking in all weather conditions, and the hourly earnings would vary with the area demand. Also, freelance delivery jobs offer no paid leaves and insurance to riders, making the job insecure at the same time.

Taking this conversation with two other research graduates, X (Mexico) and Y (Ethiopia) (they chose to keep their identity anonymous as it can affect their jobs), at the University of Copenhagen gave me a different picture of precarity. Having completed their master’s recently, they are now into job-seeking as they do part-time jobs to support themselves.

X has experience working on agroecology and has taught in Mexican schools. Whereas, Y has considerable experience working as a research assistant in Ethiopia. X is now on an establishment visa, while Y is still on a job-seeking visa. Like most foreign graduates, they too find Danish a barrier to finding relevant jobs.

Replying to my question on how easy it is to get a job here, Y says, ‘Well, it is difficult to find relevant professional jobs in Copenhagen. But there are plenty of odd jobs you can get’. In his opinion, knowing Danish becomes a barrier only if one’s discipline demands engaging with the public. He says, ‘People working in the IT field won’t find Danish a barrier, but someone whose job requires dealing the customers will find it a barrier’. Y, who is now working as a part-time office cleaner, finds the job transitory. He finds the wage too low and is worried if he would be getting enough once they start deducting regular taxes. Also, his company sends him to different locations whenever there is a shortage of labour. So, he finds the job unstable and not beneficial to his career in any way. Responding to my question about why he still sticks with the job then, Y laughs out saying, ‘Ohh I can relax and contemplate the concepts, problems, and theories in my field of study as I clean. I can’t do that on the road when I bike’ (referring to food delivery).

Given his interest in cooking, X had kitchen jobs as his first choice when he started looking for part-time jobs. Like Y, he also shares the same feeling that he doesn’t belong where he’s working now. He says, ‘I’m over-qualified to work as a kitchen assistant, and therefore, my employer doesn’t take interest in changing my position nor training me in doing other tasks as he’s doubtful of me leaving the job if I find something better’.

It’s very concerning that graduates doing odd jobs face this problem of professional and social integration. Being over-qualified makes these graduates inconsiderable when it comes to training or promotions. So even if they show an interest in a career change, their over qualifications can thwart them from such transitions. Also, part-time, or temporary employees feel left out as they are never called for staff meetings or events. Thus, such conditions trap them in precarious jobs, shutting off their chances to socialize and explore the possible ways to change their career. As discussed in the beginning, the establishment visa conditions prevent early graduates from taking up jobs outside their discipline even if it is a professional job. Don’t the international graduates deserve a fair chance to explore the Danish labour market? Shouldn’t the government think of revising its integration schemes? Even though the immigrants contribute significantly to the Danish coffers, it is so disappointing to see international graduates denied an equal and fair chance to establish themselves in the country.

Krishnanunni Mavinkal Ravindran has a MSc in Sustainable Tropical Forestry, University of Copenhagen