DDRN.dk earlier covered the intervention of Professor Maria Eriksson-Baaz, Uppsala University, Sweden, during the roundtable ”Development Thinking in Flux – Continuity and/or Change” at the DevRes 2021 Conference. In this interview, Maria Eriksson-Baaz responds in writing to a series of questions by DDRN.dk to elaborate her call for a critical focus on the aid industry and for decolonizing research.

Give an example of efforts to decolonize a full research process from fieldwork to publication

Clearly, there are examples out there. Yet, given that experiences of, and descriptions of research processes, often differ depending on who you ask, and that there is a tendency to portray things in positive light, I refrain to talk for others and give an example.

I have not done it myself. The closest I have come to it is a forthcoming edited book (2022) Facilitating researchers in insecure zones: Towards a more equitable knowledge production at Bloomsbury, edited by Oscar Abedi Dunia, James B.M. Vincent and Anju Oseema Maria Toppo – that I am facilitating now together with Swati Parashar and Mats Utas. It is a book where “facilitating researchers” from the DR Congo, Sierra Leone and India write about their experiences of working with contracting researchers mainly based in the Global North. By “facilitating researcher” we refer to the people otherwise pejoratively named research assistants or even fixers, who are based in the research setting, perform research tasks and regulate the access and flow of knowledge between “contracting researchers” and research subjects. In the book, which bears witness to marked inequalities and even exploitation, they recount the various and crucial roles that they occupy in the field and how they still most often are systematically erased and made invisible in the final research texts.

So, at the outset, this project and book might be seen as an example of decolonized research. Yet, it is still to a large extent an outcome of, and reflects the very processes, structures and relations that the book problematizes and seeks to challenge. Although clearly inspired by conversations with facilitating researchers in the field, the proposal was conceived by three Northern based researchers (me, Swati Parashar and Mats Utas) and the project funding is managed by us and Uppsala University. The participatory set-up with close collaboration with former or present facilitating researchers in the DRC, Sierra Leone and India was outlined in the project proposal. Yet, the particular researchers – Oscar Abedi Dunia, James B.M. Vincent and Anju Oseema Maria Toppo -were engaged only after the project was granted funding. So, and similarly to many other projects, the set-up was not a result of a true collaborative effort to begin with. The methodology of the project, timelines and budget-lines, including salaries were decided by us, the three Northern based researchers. Also, previous experience from sitting in such review boards suggests that few, if any at all, questions were asked about the role and influence of the non-identified “facilitating researchers” in the project, or whether the financial remuneration proposed to them was fair and sufficient.

How did development researchers in Sweden react to your views on the future of Swedish development studies?

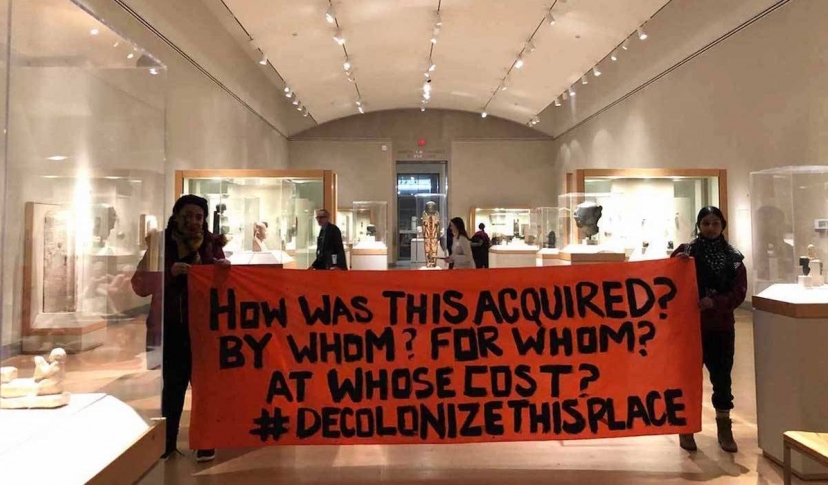

I guess you are referring to the talk at SweDev? [Swedish Development Research Network] I argued that development studies, as it is practiced and funded, basically can be described as covering two areas: firstly, and in theory, development/poverty, but which in practice has been translated to be any phenomenon in the Global South and, secondly, the politics and workings of the “development industry”. I suggested that we – as a result of the long-term post/de-colonial critique of development studies as well as the undoing of distinctions between “a developed North versus an undeveloped South” both in terms of the policies of the SDGs and a changing global landscape – should reformulate development studies as a field that mainly analyses the vast development industry and that we also really work at globalizing the other disciplines.

The reactions depend of course in part on perspectives. Many mainstream scholars who see no major problem in dominant framings of development studies are clearly less enthusiastic than more critical postcolonial scholars. Yet, irrespective of the perspective, a main challenge is that scrapping development studies as we know it would come with costs. It would most probably mean that research and teaching on all issues in the Global South at universities in the Global North would diminish radically – since such research and teaching tend to be systematically devalued both at universities and by funding bodies. In short, it would risk increasing an already problematic Eurocentrism both in teaching and research and that is of course the real dilemma, also for post-colonial scholars.

Yet, as I argued, there may also be a decolonizing potential here as we would see less of the traditional pattern of white and northern based researchers and self-proclaimed experts conducting research on, and talking on behalf of, people in the Global South. And given all the important and well-informed research conducted in the South on issues related to sustainable development and poverty, I cannot imagine it would imply a large loss of vital knowledge.

A few disciplines have ‘globalized’ early, possibly as identified as strategic ‘keys’ to poverty reduction, e.g., education, health, focus on women. How has it affected the community of development research?

I guess by globalizing early you refer to research areas that address North-South relations or address a particular theme in empirical contexts both in the North and South? In that case yes, some disciplines and areas are more globalized than others, such as for instance gender or feminist research, or health, as you mention. Yet, there is still a tendency of othering also in those fields, whereby research conducted in the Global South is cast as different.

For instance, in recent years I have conducted research on issues such as militarized masculinities and army wives in the DR Congo. Doing such research, you always have the sense of being the odd one out at mainstream conferences and journals and you get a particular kind of questions from discussants and reviewers, not seldom with a tint of exotisation, which perpetuate the otherness of the research subjects and contexts.

Also, both in terms of courses/teaching and research, such research still tend to be labled or placed under the rubric ”development studies”. Also, the term ’global’ itself seems to in practice have replaced development somehow, signalling a focus on issues in the Global South, rather than a truly global focus.

What kind of instrument in research policy may encourage disciplines to go global?

In general, it would of course be important for research funders to clearly and explicitly signal in the calls both to reviewers and applicants of research funding that the focus is global. Yet, given that research on issues in the Global South tend to be systematically devalued, there is still a risk that research on issues outside the North would still be devalued. Having more diverse review committees with more reviewers based in institutions in the Global South could be important to counteract such tendencies.

Yet, a more pressing problem is the funding structure itself, which reproduces North-South inequalities in research. In short, most research funding for research in the Global South tends to be available only for researchers in the Global North, creating problematic and systemic power inequalities. Even if we can and are often encouraged to partner with researchers and institutions in the country of research, the research funding is still managed by researchers in the Global North which in turn reproduces the power inequalities. For instance, earlier this year, African scholars wrote an Open letter to international funders of science and development in Africa in the journal Nature. They cite the example of malaria research where only 1% of malaria funding is made available to in-country research institutions. Changing these funding structures that systematically favor universities and scholars in the global North is really crucial if we are to decolonize development research.

While DANIDA administers a separate grant facility altogether, the SIDA facility is integrated in overall research council system. Which are the advantages and disadvantages of either framework?

Yes, research funding to development research in Sweden – which is different from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida’s) support in strengthening research capacity in the “partner countries” – moved from being administered by Sida to being administered by the Swedish Research Council around 8 years ago I think. As far as I understand it the move was a result of an effort to make the funding more effective and professional, by letting it be managed by expert institutions in research funding.

This move did not change much in terms of the processes and content of research though. The review process was conducted by independent researchers/reviewers also when it was managed by Sida so the topics funded were not decided or connected to the operational work of Sida. The funding is still formulated as research that “is of particular relevance to the fight against poverty and for sustainable development in low-income countries”. This directive was and is still interpreted in a very broad way and includes, more or less, any research topic that somehow connects to a low-income country.

Does the current ‘woke’ movement threaten independent research?

I think the concept woke research itself is deeply problematic, used and abused in so many different ways, so I refrain from using it myself. What I can say is that we in Sweden and also in Denmark as I understand it – for quite some time now – see attacks on critical scholars both from the public and mainstream research and forums as academic rights watch – accusing critical scholars for limiting academic freedom and independent research. Academia is, according to such voices, taken over by supposedly extreme and politically correct feminists, anti-racists and LGBTQ+ people.

This line of attack against critical scholarship is clearly a worrying trend from various perspectives. It follows the very problematic assumption that there exists such a thing as objective and value-free research, which they represent themselves. Academic freedom is invoked to defend the right to use discriminatory language and concepts or to refuse to reflect upon more inclusive teaching and course literature, rather than the very tangible threats against academic freedom and independent research that we see globally, enacted by repressive states, climate change denial lobbying groups, right wing movements as well as other actors.

Which should be the main priorities for critical studies of the aid industry?

Clearly, one of the most crucial priorities would be to focus on the politics, policies and interventions around climate change, from a climate justice perspective which highlights inequalities within and between countries in terms of responsibility for and vulnerability to climate change. More research on that is sorely needed in development studies.

Analyzing how various development actors handle that is important– not the least development NGOs and Foundations that have become increasingly powerful actors, receiving a large bulk of development finance. Clearly, the sector faces particular challenges for the task ahead given their traditional orientation to locate problems in and combat poverty and other suffering in the Global South. In so far as responsibility of the Global North has been evoked in the sector, it has mainly been framed as a responsibility to help fellow humans in need elsewhere. Given this history and legacy, how will they address the need for climate action in the Global North?

The need to emphasize climate action in the global North appears particularly challenging given the increasing marketization of development actors, the ways in which they – in the wake of New Public Management and neoliberal reforms – adapt more business-like organizational structures, rhetoric and goals. Research on environmental NGOs already indicate that they have often refrained from advocating climate action that bears direct consequences for funders and supporters, in order to guarantee and sustain funding. Clearly, the message ”you need to change your life-style” is a difficult fundraising strategy, difficult to sell. So how will more traditional NGOs handle this? In general, I also think more research into the consequences of the increasing marketization of the sector is warranted, as it risks having other detrimental effects, including even less co-ordination, as well as a tendency to reproduce white-saviour tendencies.

I also think that more attention is needed to both South-South development cooperation and the agency of development aid partners and receivers. I, together with Swati Parashar, in a recent short text in International Politics Review argued that we as critical IR and development scholars have a tendency to reproduce Eurocentrism ourselves and that we have been slow in querying changes in the global landscape. We still have a tendency to focus on development actors in the global North and take their discourses and policies as the point of departure for critical inquiry. We also often have a one-sided focus on the governing of such actors and fail to attend to the agency of those intervened upon. Through this, we risk bloating the power and influence of the Global North but also, and quite problematically, imputing classical colonial imageries of passivity on Southern actors.

Also read: The Neo-Colonialism in Development Studies

SUPPORT DDRN SCIENCE JOURNALISM. DONATE DKK 20 OR MORE![]() (APPLICABLE IN DENMARK ONLY)

(APPLICABLE IN DENMARK ONLY)

Maria Eriksson-Baaz

Maria Eriksson-Baaz