On November 17, 2023, the Danish NGO Nunca Mas celebrates its 10-year jubilee. Having implemented a range of human rights projects with NGO partners in Ecuador, Honduras, the Philippines, Sri Lanka and Zimbabwe. Nunca Mas and its members can review the experiences gained within an area of intervention, which often is overlooked.

DDRN has previously reported on the work and the particular psycho-social approach of Nunca Mas. In this article, we focus on the most recent activity completed jointly with the Philippine NGO Centre for Disaster Preparedness Foundation (CDP).

During the past seven years, government forces have stepped up their curtailment of democratic practices in the Philippines. Crackdown on groups critical to the government has created a human rights crisis. The global pandemic and extreme weather events have worsened this situation, as the government is using these crises as a pretext for tightening the repression towards voices of opposition.

Red-tagging was first implemented in 1969 as a government-backed campaign to counter communist and Maoist groups, particularly the New People’s Army (NPA). Red tagging has since become a destructive tool to quash dissent. Under the former Duterte government and his National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC), the regime has used the guise of red-tagging to crack down on activists and dissidents.

As an example, the Human Rights Foundation has documented Frenchie Mae Cumpio, a 24-year-old Philippine community journalist and executive director of the independent news website, Eastern Vista, as one of the many journalists “red-tagged” by the Philippines regime.

Amnesty International has highlighted that the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights along with human rights organizations have called for the immediate end to this approach. The concern is that the government’s dangerously broad counter-insurgency strategy has led to an increase in human rights violations against human rights defenders and political activists across the country.

Human Rights Watch has pointed to the intimidation of indigenous leaders and activists opposed to government-backed projects in the Philippines. Again, those resisting projects are accused of being fighters or supporters of a communist insurgency. The red-tagging contributes to making the Philippines one of Asia’s most dangerous countries for environmental activists and land defenders.

Efforts to counter the strategy of ‘red-tagging’

The Danish NGO Nunca Mas has in the past few years completed two civil society interventions (in short: Defend 1 and 2) in the Philippines jointly with the Centre for Disaster Preparedness Foundation (CDP).

CDP is a pioneer and a recognized civil society actor in the Philippines for community-based disaster risk reduction and management. CDP works with community-based organizations, the private sector, government agencies, and various non-governmental entities, including faith-based institutions, and the academe. CDP is one of the CSO representatives in the policy-making body, the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC), which is enshrined in Philippine law.

The interventions have been funded by a grant from the Danish umbrella NGO Civil Society in Development (CISU) The objectives of the first intervention were (1) to provide technical support to CSOs, partner government agencies, and community-based groups on policy advocacy, and (2) to create space for dialogue and collaborations with networks and grassroots organizations on human rights. The second intervention focused on (1) para-legal support for human rights defenders and local humanitarian organizations, (2) continuous capacity-building and technical support in terms of lobby, advocacy, and policy dialogue, and (3) mental health and psycho-social support for partner CSOs affected by human rights violations.

While Nunca Mas has been steering the partnership, CDP has been directing the implementation and national collaborations. One important lesson learned during the two interventions has been the challenge of finding suitable and regular staff. Many human rights defenders are highly vulnerable regarding security and mental wellness. And regular development workers may not find high risk projects appealing due to the threats existing against CSOs.

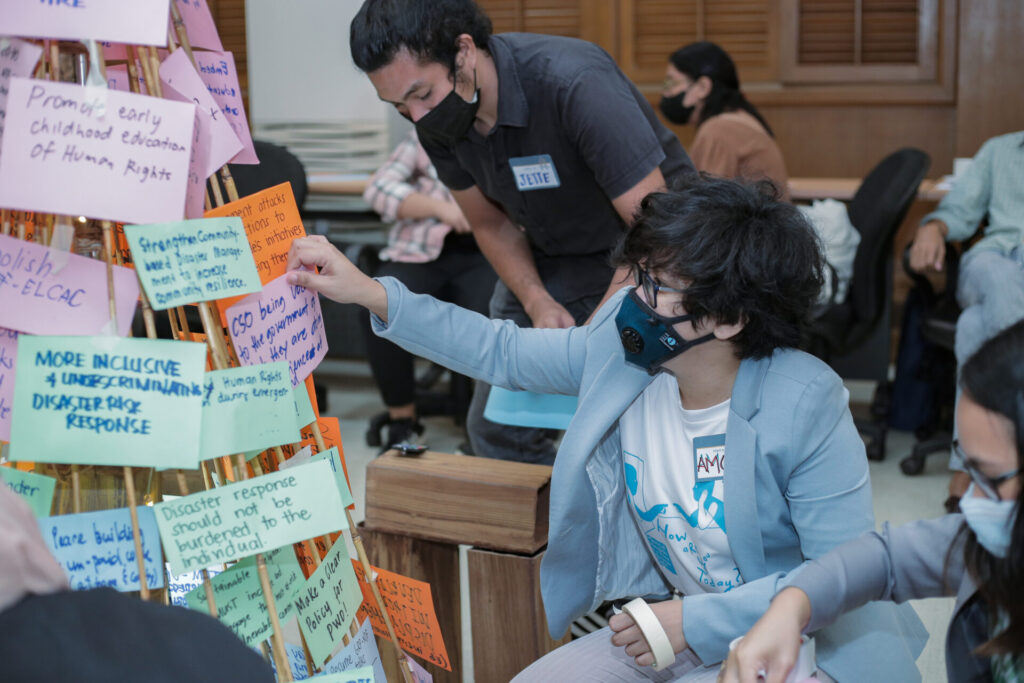

During the concluding conference of Defend 2, which was held on 28 November 2023 in Quezon City, Philippines, a particular method of discussion was adopted as reflected in the title of the conference ‘Campfire Conversations on Human Rights and Development’. The discussion brought together representatives of the three target groups for the interventions: (1) Disaster Risk Reduction Management and human rights CSOs networks and partners; (2) Youth and academic institutions; and (3) other socio-civic and peoples’ organisations.

The Bonfire and the Torch of Hope

In the centre of the room, an art installation representing a bonfire is placed. The facilitator of the conversation will open the campfire and distribute ‘kindlings’ and ‘firewood’ to all participants. For each kindling an issue or concern will be written on a metacard based upon participants’ advocacies. The issues and concerns may lead to bigger more complicated problems or risks, thus representing ‘firewood’. ‘Kindlings’ and ‘firewood’ are then attached to the ‘bonfire’ by the participants.

The sharing of issues and concerns are organised into four different themes, each of which is introduced by a ‘fire starter’. The themes are:

- Community building, presented by Ms. Luz Malibiran, Executive Director of Community Organizers Multiversity

- Human rights, presented by Mr. Gary Granada, Executive Director, House of Shareware and LAPIS

- Community-based Disaster Risk Reduction Management (DRRM), presented by Ms. Kriszia Lorrain Enriquez, Advocacy Convenor, AGAP BANTA

- DDRM policy advocacy, presented by Ms. Ma. Bernadette Uy, Communications and Information Coordinator, ACCORD

Following the sharing of ‘campfire stories’, a Torch of Hope will be ‘lighted’ marking the end of discussions.

The next steps include that the results of each thematic conversation serve as a resource by CSO networks, as they put forward policy recommendations to national and international bodies about risks and needs to be addressed by these bodies:

- The high risks faced by civil society, community-based organizations, and local humanitarian actors and rights defenders in the Philippines.

- The need to nurture and enable community-led innovations, development of solutions, and accountability mechanisms; and

- The need to uphold and implement a more inclusive process in formulating development plans, programs, and policies amid shrinking civic space.

The Philippine NGO Centre for Disaster Preparedness Foundation (CDP) and the Shareware School have jointly produced the video ‘One-hour crash course ‘Learning Human Rights’ for young people.

Peter Vedel Kessing, who is a Senior Researcher, Ph.D., at the Danish Institute for Human Rights; a Member of the UN Torture Committee; and a member of the Danish National Preventive Mechanism NPM (OPCAT) visiting places of detention since 2009, contributed advice to the production of the video.

Since 1997, Peter has worked with international projects on the prevention of torture and inspection of places of detention in several countries in Asia, the Middle East, Europe, and Africa.

We asked Peter about his assessment of the video:

- Who are the primary target group(s) for viewing the video?

The primary target group is primary and secondary school. In the current human rights situation, authoritarian states are on the rise often giving a false and very negative one-sided picture of human rights. The video is an important endeavor to give a broad and more nuanced picture of human rights and it is important that coming generations and new leaders have a correct and more nuanced understanding of the scope and content of international human rights.

- Based upon your experience from projects in a range of South countries, how well do content and format meet the needs of the target group(s)?

The material is very broad and covers many different human rights. The rights are explained in an interesting and very easy understandable way. With practical and illustrative examples. I believe that the material possibly with minor adjustments could be very useful in other settings.

- The video is produced for an audience in the Philippines. What kind of adaptation would be needed to produce a version for a different country?

Maybe some of the illustrative examples on human rights would have to be adapted to the specific country.

- How well does the video encourage live discussion among the viewers after each of the three parts?

It is really a strength that the video is very inter-active and encourage discussions.

- Any suggestions for improvement of the current video, or for the production of a second video with a different content/approach?

The video seeks to cover almost all human rights civil, political, economic, and social and is very broad. It could be considered in a possible second edition to narrow the focus a little and focus on the rights that are most relevant in the specific country.