When the Colombian government and the guerrilla group FARC signed the peace deal back in 2016, it was only the beginning of a long road towards a, in theory, more peaceful country after four decades of armed conflict. Part of the peace accords involved creating a system of truth, justice, reparation, and non-repetition. The National University of Colombia made agreements to assist in that process as a trustworthy, neutral actor.

Each campus has developed different strategies, such as supporting the writing of reports, working directly with the Truth Commission, or supporting communities in the process of recovering memory. All of these have been issues that the university has addressed through research groups of specific professors.

In the case of the national university in the Department of Cesar, the La Paz campus has supported ten different communities in the recollection of information and the writing of special reports to the Special Justice for Peace.

“We are on the difficult task of overcoming war and building peace in the territory. What is important now is not the paper of these peace agreements, but how people in the local areas are taking over the results of these agreements, how people are living, and what people are doing to build reconciliation. This is the exercise that the University’s Peace Laboratory is doing,” explains Anthropologist, Professor Lucia Eufemia Meneses, who directs the so-called Territorial Peace Laboratory at the La Paz campus.

Armed Conflict in El Toco

One of the communities supported by the National University is El Toco. Let’s take a closer look at its history related to armed conflict.

Toco is a mountainous place, very suitable for livestock farming and for growing all kinds of crops. A group of farmers arrived in El Toco from several places in 1991 in search of land to work on. In 1996 they succeeded in getting ownership of the land. They had two primary schools, one secondary school, and a shop in the village.

In April 1997, the first massacre by the paramilitary group AUC (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia) hit the village of El Toco. Many of the villagers fled. One month later, the next massacre occurred: eight people were killed, and even more people left. And three years later, another three persons were killed in El Toco. Unfortunately, this is the story of many, many places in Colombia during the decades-long armed conflict. The country has the third highest number of internally displaced people – after Syria and Ukraine.

According to the Truth Commission, which also was created as a result of the peace process, from 1995 to 2004 more than 8 million hectares were dispossessed or abandoned. The inhabitants of El Toco are now still fighting to get back their land, which they were displaced from 25 years ago. The so-called land restitution basically means returning illegally held land to its rightful owners.

Patterns of Macro-Criminality

As stated by the National Victims Unit, between 1997 and 2003, more than 57,000 people were forcibly displaced and 6,000 killed in the municipalities of the central part of the department of Cesar.

Miguel Ricardo Serna is the leader of the victim’s organization, Asocomparto, from the community of El Toco. He was an inhabitant in El Toco from 1991 until 1997, the year in which the paramilitaries entered the place, killed two people, and forced the peasants to leave their land. Since then, Miguel has been living in the capital, Bogotá, and also in the nearby municipality of Codazzi.

“It was like a romance of peace. We were living in that territory from 1991 to 1997. We had eighty families organized in a working committee, there was a women’s organization and we belonged to a farmer’s organization, too,” recalls Miguel as he sits together with several other former inhabitants of El Toco. We meet just outside the city of Valledupar, in the municipality of Codazzi, where Miguel is living nowadays, some 30 km away from El Toco.

In the case of El Toco, the National University hired two professionals who, together with the victim’s organization, worked with the information for the report, organized it, and helped write it too. For the leader of the Territorial Peace Laboratory, it was an extremely important task:

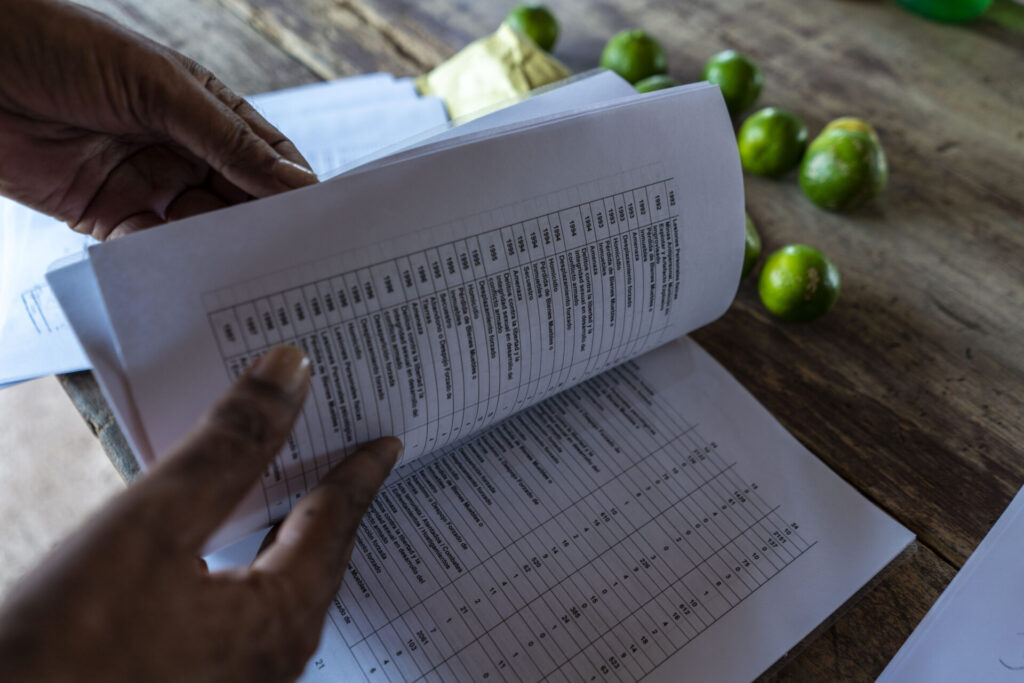

“Without the support from the University and non-profit organizations, it is almost impossible for these communities to present the reports to the Special Justice for Peace. The real support has been in analyzing the information, putting it into the basic formats requested – and presenting it in a way that is intelligible for the task that the Special Justice for Peace does, which is to find patterns of macro-criminality that allow the guilty to be found and brought to justice. The reports help find these patterns, and organize the information in such a way that there is a revision of these patterns of macro-criminality. The task of the University is to organize and analyze the information to present it in this way, by actors in the conflict, by temporalities, by victimizing events, etc. That allows the information to be intelligible and serve to identify these patterns,” explains Lucia Eufemia Meneses.

The local leader from El Toco, Miguel, will never forget that day in April 1987 that forever changed the lives of the people of the village: “It was something so beautiful until April ‘97, when that happiness came to an end because the paramilitaries arrived and killed two people and displaced us from the territory. It was something like a very big void for the community because we lost the social fabric and the life project we had been working on for several years. It was the biggest rupture of our lives, and we didn’t understand what was going on behind all of this,” tells Miguel.

Only one month later, paramilitaries killed another eight people in El Toco: “That was the biggest chaos in the community of El Toco, because we didn’t understand what was going on behind that war, behind those masks, because the paramilitaries showed up and there were some people who had their faces covered as we do now during the pandemic. So they would point out that this is the leader that is called so-and-so and that we were guerrilleros,” remembers Miguel.

Miguel Ricardo Serna recalls these painful moments of his history and the history of El Toco, in his backyard in what became his home in the municipality of Codazzi. Several other former inhabitants of El Toco are here too, and still, tears fall as they together make this journey through their difficult past, as they have been doing together with the National University. This is also a healing process for part of the millions of victims of the conflict, trying to conciliate and construct a future in peace after decades of violence.

”It is a report which shows the whole process of historical effects that have occurred, and the revictimization that the people of El Toco have suffered. The reports of the special Justice for Peace must follow a specific structure, narrate the affectations in a certain way, time and place, and can annex info of all times. In the case of El Toco, they narrated everything that had happened and contributed all the info they had through maps and topographies to be able to understand all the specific affectations,” explains Lucia Eufemia Meneses, from the Territorial Peace Laboratory.

Furthermore, the reports also serve to show the University’s commitment to the region: ”And it shows how we’re committed to the construction of peace on a small scale and that has helped the communities of the Department of Cesar – to feel that they have an institution that supports them and that is committed to territorial peace,” says Lucia Eufemia Meneses.

Land Restitution Efforts Are Stumbling Along

After the displacement by the paramilitaries, it became known that the local population had been forced to ”sell” their land to members of those groups for small, symbolic amounts like three million Colombian pesos, and then shortly after, the same paramilitaries had sold the same land to the multinational mining firms, Drummond and Prodeco, for millions of millions of pesos. Those companies have been involved in carbon mining in Colombia and in the Cesar department for many years.

Already in 2011, Colombia passed its Victims and Land Restitution Law 1448, which is about returning illegally held land to its rightful owners. The Land Restitution Unit was also established. Basically, this law was also about recognizing the victims of the armed conflict in the country. But in the first ten years since the law was enacted, less than 10 % (around 500,000 hectares) of the restitution goal has been reached

In the case of El Toco, several of the land restitution applications have been rejected. Some of the victims have also been offered money to cancel their restitution reclaim.

For the leader of El Toco, it is something really close to his heart that the State recognizes the victims of the village and gives them back their land, which was violently taken away from them during the armed conflict. “This is about the dignity of our community; it is the dignity of a people. So today these people, represented in the community, ask the whole world to continue investigating the struggle of the victims, because we need it, here out in the corners of the countryside in Colombia.”

The reports from the ten communities in the Department of Cesar and in the southern part of La Guajira, created with support from the university, were handed over to The Special Justice for Peace at an official ceremony at the La Paz campus.

Lise Josefsen Hermann – a freelance journalist based in Latin America for more than a decade. She is a Pulitzer Grantee, works for the investigative media Danwatch and has published in media like Al Jazeera, BBC, Deutsche Welle, Danish Broadcasting Corporation, El Pais, New York Times, and Undark Magazine. Photo: Charlie Cordero, Cesar, Colombia.

Miguel Ricardo Serna, leader of the community of El Toco. Migue was an inhabitant of one of the plots of El Toco from 1991 until 1997, the year in which the paramilitaries entered the property, killed two people, and forced the peasants to vacate their land. Miguel went to live in the municipality from Codazzi and then to Bogotá.