Indigenous peoples of the Amazon are affected by mercury contamination in Bolivia due to small-scale gold extraction. The women are some of the most vulnerable – and at the same time the ones handling the mercury most directly. Is there a possible alternative?

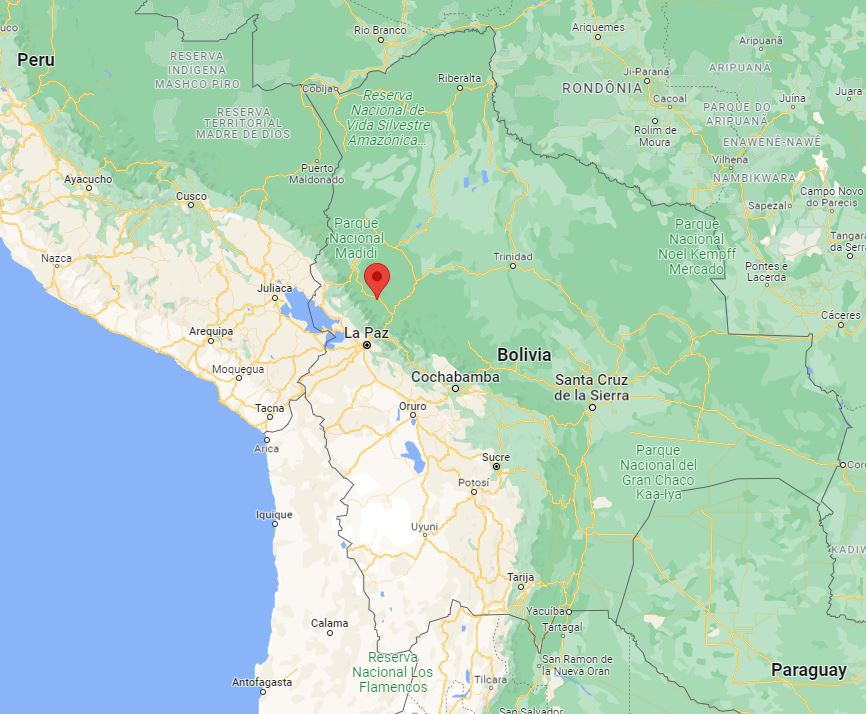

The roads are crooked, and the vegetation is overwhelmingly green. Here the surroundings of the village of Guanay dominates tropical rainforest and a jumble of green shades. But then again – in this part of the Bolivian Amazon, most people think of anything but trees and plants. All they think of is gold. Gold fever is raging, and big machines are working at full speed, degrading the landscape indiscriminately.

While the poisonous heavy metal, mercury, is banned in many of the world’s countries, it is still legal for use in Bolivia. Hence, Bolivia is the largest mercury buyer in the world according to official statistics. According to the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) in 2020, gold mining in Bolivia discharges around 100 tons of mercury per year into rivers. The UN officially criticized Bolivia on this account. During the 183rd session of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), which took place in December 2021, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Toxic Substances and Human Rights, Marcos Orellana, urged the Bolivian government to present its plan of action to reduce the use and commercialization of mercury in extractive activities.

The Special Rapporteur warned that the increase in the use, commercialization, and trafficking of mercury from Bolivia to countries in the region not only frustrates the efforts of the international community to comply with the Minamata Convention but also generates a serious regional problem in South America. The UN Minamata Convention on Mercury entered into force in August 2017 and is an international treaty designed to protect human health and the environment from anthropogenic emissions and releases of mercury. It is named after the Japanese Minamata bay, where in the Mid 1900s mercury tainted industrial wastewater and poisoned thousands of people, which became known as the Minamata disease.

Juan Carlos Almanza is responsible for a project promoting mercury-free gold mining in Bolivia and which is being implemented by the Plagbol Foundation, with funding from the Danish NGO Dialogos. He is highly worried about the situation with mercury in his country:

“I imagine that something like what happened in Minamata is going to happen because Minamata released 5000 tons of mercury in the factory. Every year we are throwing out a similar amount. Every year. I think that in 20-30 years, the consequences are really going to be terrible and not only for us. These rivers reach the Amazon, they reach Brazil and from there they flow into the Atlantic, so the issue is going to be quite complicated. Our main objective is to make the general population aware of the damage that mercury has caused and to look for alternatives for gold production by reducing or eliminating mercury,” says Juan Carlos.

The Bolivian Amazon is being seriously affected by small-scale gold mining and the human rights of the indigenous peoples in the area are being violated by mercury contamination from this gold mining in their rivers. Indigenous women have learned to extract gold practically from the waste of the companies. One of them is Kenia Argandoña Machicado, 38. She belongs to the indigenous Leco-people, from the village of San José de Pelera, near Guanay. She and her partner have been miners for all her life – and so have her parents She recalls when they began to use mercury around her seven years ago: “We began to use mercury when they started to extract gold by means of machines around here,” Kenia tells.

With naturalness, she shows us how they – everyone – is using mercury as a part of their daily routine in gold mining. With mercury, they get to catch all the tiny bits of gold that they get from panning the sandy material from the river. Mercury is mixed with the material containing gold. A mercury-gold amalgam is then formed. When heated, the gold remains – one of the problems is toxic fumes from the mercury.

“With mercury, not even a spark is lost; on the contrary, everything is rescued. With most of it we use mercury because we don’t know about other ways, so that’s all we do. We find the gold in very tiny bits. That’s why the mercury was brought here for the miners to be able to catch the gold. Before all this gold-digging, the area had crystal clear rivers with fish. We don’t have that anymore, we can’t fish in the river anymore,” tells Kenia.

But there are alternatives to mercury, and in Guanay they are beginning to grasp that. Now they are receiving workshops from the Bolivian organization Plagbol, supported by the Danish NGO Dialogos teaching the miners how to use borax (sodium tetraborate) in the gold extraction process as a much lesser contaminating matter than mercury. Borax is often used as a component in laundry detergent and is a combination of boron, sodium, and oxygen.

Part of the workshops also teaches about health risks. Mercury vapour affects the nervous, digestive, and immune systems as well as the lungs and kidneys, and it can be fatal. It can be felt from inhalation, ingestion, or even just physical contact with mercury. Common symptoms include tremors, difficulty sleeping, memory loss, headaches, and loss of motor skills. Most people in gold extracting areas in Bolivia – such as Guanay – do not know a lot, if anything at all, about the risk of using mercury. In addition to this, mercury can be bought freely in many shops throughout the country, without special permission.

”We didn’t know anything about the risks of mercury, nothing. Now that the Internet is accessible for us out here, we can learn about it but can you imagine how it was five years ago? Now we can search Google for it, for instance. Now we know that mercury is harmful. Even sometimes we would be handling mercury while eating because we didn’t have the knowledge that this substance was harmful to us,” says Kenia.

”We no longer burn wherever we go, but everyone uses it in this sector. It is bad for us, but it is a necessary evil that we also need to extract the gold,” says Kenia. She is happy about the fact, that there will be workshops for the miners, where they learn about alternatives to mercury and about how to handle it in a safer way.

”Mercury is harmful for us, we now know more than before, we didn’t know that. Because what is going to happen to the children, sometimes to the children of the people who are pregnant when they inhale that air with mercury. We are damaging the fish, we are damaging the river, we are damaging all those things and that is a big concern for us,” Kenia says.

“For us here in Pelera the gold is very important because we live off this material. Here, most people do not dedicate so much to agriculture or livestock anymore, because there are no sectors for the area of livestock for the area of cultivation. Well, we have land, but the people have become accustomed to what is gold, and we no longer work in agriculture,” says Kenia.

This is a common consequence of gold fever, everyone dedicates themselves to looking for gold, and do not plant their own food anymore. That makes people totally dependent on money from the gold – which at some point disappears – and leaves the local population with a big problem – besides the contamination issues.

We return to Juan Carlos Almanza from the Plagbol Foundation: “The problem is that gold is not renewable; in other words, the gold runs out, as we have seen in some communities, and people either migrate to the city, or they live in very poor conditions, so this is a very complicated situation. You can see here in Guanay, that the environmental damage caused by this mining is terrible. That land, it costs a lot to recover, the companies do nothing about Social Responsibility; they extract, they finish, the gold is gone, and they leave and leave everything destroyed,” says Juan Carlos.

In Bolivia, there have been environmental regulations in place since 1997 that require gold mining that uses mercury to recover it. However, the government itself has acknowledged that 90 % of the gold mined in Bolivia does not recover mercury, it just flows directly into the rivers. And it is evident how mercury poisoning is affecting the indigenous communities, their rivers and the fish that are part of their diet.

One of the few existing studies about mercury pollution in Bolivia was published in June 2021 by International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN). It examined mercury levels in women in child-baring ages in Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, and Venezuela. It found that indigenous Bolivian women have extremely high mercury levels in their bodies. More than half of the participants in the study exceeded the established United State Environment Protection Agency threshold level at which negative effects on the development of the fetus begin.

People in the villages tell that they experience more children being born with some kinds of cognitive issues. For instance, in another gold-extracting area in Bolivia – Sorata – we talk with Milton Yujra Mamani – a school director who simply says that during his 15 years in the position he experienced that there was e a higher number of children with so-called cognitive issues: “Yes, we have a problem with mercury, and it is really serious. It is accumulating here. Most of the children here are children of miners. We have more students with difficulties and handicaps. There are more cases than earlier on. We are worried that it is due to mercury,” says Milton Yujra Mamani.

And the situation with mercury in Bolivia worries the country’s own Ombudsman’s Office – Defensoría del Pueblo: “The material, technical and economic conditions do not exist in the country to protect human health and the environment from anthropogenic mercury emissions produced mainly by gold mining, whose importation has grown steadily and exponentially, despite the fact that it is a highly toxic metal”, said the Ombudsman, Nadia Cruz on 3rd of May 2022.

Because of the nature of mercury, the most serious effects of its contamination will not be seen for several years. It is a silent death of these peoples of the Bolivian Amazon generated by the gold fever.

“There are tons of mercury that we import every year and there is no standard that tells you how to work with mercury and with which precautions. So, a large part of the mercury used every year is going into our rivers and the consequences are going to be terrible later,” says Juan Carlos from Plagbol.

In many countries, according to the Minamata convention, there are restrictions on buying mercury or it is prohibited. But in Bolivia, everyone can just go to the shop and buy mercury, without further ado. At the same time, mercury is in the top 10 chemicals of major public health concern according to the World Health Organization, (WHO).

He is especially worried about the women, Barranquillas like Kenia. So, in their projects and workshops they mainly work with this group. “They are a vulnerable group because they are women in the fertile stage. They can harm their children while they are pregnant or just by the fact that they are contaminated. It is a very vulnerable group and we must work hard to avoid this,” says Juan Carlos.

He is also concerned about the lack of studies and documentation about this serious situation: “There are no scientific studies here in Guanay that determine the contamination of the water. And when we have made a study in the health sector, not even the doctors are informed about the damage it is causing to the population, nor are they able to identify a person who has some type of chronic intoxication caused by mercury. We need studies. But we have seen in some towns that there are already some people affected and among the communities themselves they mention it to us. Yes, I know a person who has these symptoms, which we can relate to mercury,” Juan Carlos tells.

This is an invisible situation that might end up really serious for the local population in the future. But making the population in the gold-digging areas change their dangerous habits is not that easy: “The interest of the population in looking for alternatives to mercury is very complicated. People often don’t believe that mercury is harmful.

The problem is that nowadays you use mercury and don’t feel any symptoms. So, people say, “no, I use it all the time and nothing happens”. But mercury is bio accumulative, so it accumulates in the body and affects you over the years. That is one of the main problems we have because it is not instantaneous damage, so there is a lot of doubt among people,” explains Juan Carlos.

By the riverside Fabiola Salas (28), a woman pregnant with her 4th child, is doing dangerous work in search of gold. It makes a strong impression to see her pregnant tummy exercising this task, knowing the serious potential risk for her fetus. She has been working with gold since she was 12 years old. Her parents were small-scale gold miners too.

“Mercury is harmful over time, all that has been explained to us. We have learned a little about this. It’s not right, this is for our own good, isn’t it? And that later it will hurt us. Because of my condition more than anything else. All that has been taught to us today. I didn’t know about those things before. This is very good to learn, how to get the gold without hurting ourselves,” says Fabiola, who has just assisted in a workshop organized by Plagbol.

“We’ve learned about how mercury can affect health, what harm it can do to us, you can get shaking, they say that it can’t hurt a brain, and all those things,” says Fabiola.

At the same time, she reckons that changing away from mercury is no easy task: “Here everybody we are still using mercury, but maybe it is difficult to change the method,” Fabiola says. She imagines a future with gold for her children too: “I think so because it is customary here, we don’t leave. My parents have been working on the same here and I have grown up here. We all live from the gold here, there is nothing else, just look for more gold, to continue to work in gold.” Fabiola ends her tale here and returns to her pan at the riverbed.

Lise Josefsen Hermann – a freelance journalist based in Latin America for more than a decade. She is a Pulitzer Grantee, works for the Danish investigative media Danwatch, and has also published in media like Al Jazeera, BBC, China Dialogue, Deutsche Welle, Danish Broadcasting Corporation, El Pais, New York Times, and Undark Magazine.

Photos: Wara Vargas, Guanay, Bolivia

Barranquilleras Women of Gold

No Man’s Land