When Dr. Norazana Ibrahim did her Ph.D. project at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU), she could confirm that agricultural waste should be an important energy resource in Malaysia. Now comes the difficult part of commercializing the technology in the Malaysian waste management industries.

In June 2010 a baby boy was born three weeks early at Hillerød Hospital in Denmark. Babies are born at this hospital every day, but in this case, his mother was the Malaysian Ph.D. student Norazana Ibrahim, who had to take a break from her PhD research to deliver a baby. Everything went fine. But:

“My studies was delayed a little bit,” Dr. Norazana says, as she sits in the dean’s meeting room at the Faculty of Chemical and Energy Engineering at UTM in Johor, Malaysia, where she now works as a senior lecturer and scientist.

About six months later she had another delivery, when she turned in her Ph.D. thesis Bio-oil from Flash Pyrolysis of Agricultural Residues.

DTU by coincidence

In 2007 both she and husband decided to do their PhD’s abroad. At that time, the Malaysian government encouraged students in engineering to go abroad to study and offered scholarships to PhD students. The couple had their mind set on Australia or England, but was open to other possibilities. They were already parents to a toddler, so one criteria was very important.

“Because we had a kid, we could not do our PhD in separate countries, so we needed to find a place with courses for both me and for my husband. And luckily we found that DTU was the one that best met our criteria,” Dr. Norazana explains.

Finding out about DTU was actually quite a coincidence. A professor from DTU was visiting UTM and gave some talks. His subject was very relevant to Dr. Ibrahim’s husband. At that point the two did not know much about Denmark and the Danish research environment. But it sounded like the perfect place for both of them, and after discussions with the head of the department at UTM, they decided to go.

There were no formal exchange programmes between UTM and DTU at the time, so the couple had to find out everything about admission and practical details from scratch. Dr. Norazana contacted the Danish professor Kim Dam-Johansen who could potentially become her supervisor, and after a while everything was settled. By that, they left Malaysia for almost four years.

Agricultural waste has great value as energy

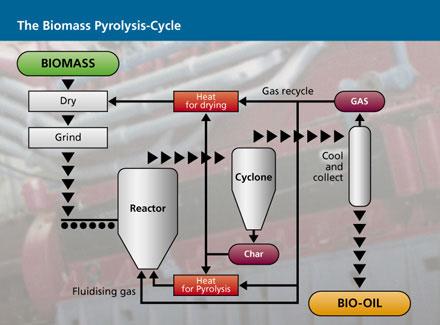

Norazana Ibrahim’s Ph.D. project was about converting agricultural waste into biofuel by thermal methods. In this case by using a flash pyrolysis centrifugal reactor (PCR). (Read about husband Mohd. Kamaruddin and his research Model-Based Integrated Process Design and Controller Design of Chemical Processes).

This is a process where agricultural residues as straw, wood and husk is heated under high pressures and the outcome is products as biochar, biooil and biogas. The output depends on the biological composition of the waste, and because of that it differs what product would be more beneficial to produce depending on what kind of waste is used.

The research made by Dr. Norazana was to determine how the process of transforming three different types of bio waste: wheat straw, wood and rice husk could be designed to get the best output. This by using flash pyrolysis techniques in a rotating reactor.

When designing waste combustion plants it is very important to customize the process to type of waste that will be the main feedstock in order to obtain the highest output. And vice versa, if a specific output is needed, it is important to know what kind of waste will be optimal.

“Agricultural waste contains a lot of ashes compared to wood. For example, if our target is liquid oil, I will suggest you to go for wood waste because it contains less ashes and has more cellulose content in wood as compared to agriculture,” Dr. Norazana says.

Wheat straw and wood are bio-waste that is common in Denmark. But to be able to investigate how typical Malaysian bio-waste would perform, Dr. Norazana also experimented with rice husk, which she had sent from Malaysia.

“I managed to post about ten kilos, and that was enough for my study. I could compare the products. Each type of biomass has different characteristics, and that will affect your product yield.”

When going abroad, students as Dr. Norazana have to consider how to benefit scientifically from the scholarship. In this case, the experiments with pyrolysis could not have taken place in Malaysia.

“We had these kind of facilities on lab scale, but during that time, we didn’t have it on pilot scale. So it was a good chance for me,” she says.

Bringing new technology to Malaysia

Malaysia has a lot of agriculture which of course result in a lot of agricultural waste. Besides rice, especially the palm oil industry produces a lot of waste. Malaysia has the second largest export of palm oil in the world, and in almost any corner of the country, you will find a plantation nearby. A lot of the waste products as leaves, rind and shells are not reused, but is placed on landfills or simply burned.

However, the waste could be reused as energy sources. Dr. Norazana is convinced, that high temperature combustion is an important way to convert biological waste in the future.

“Nowadays most countries, especially developing countries, really depend on fossil fuel. The consumption gives a tremendous effect on the environment because of the emissions. Plant waste is an alternative that can replace coal and fossil oil, and we have many methods to convert waste into suitable products. I prefer the thermal chemical method, since it is a fast method to convert waste or any solid waste into bio fuel. As compared to biochemical methods which involve enzymes, yeast and bacteria, which is time consuming,” Dr. Norazana says.

After her return in 2010, Dr. Norazana started to collaborate with other lecturers at UTM to apply for funding and exhibit the research on thermal combustion to the Malaysian waste management industries. Based on her studies in Denmark, she could demonstrate at least three useful products that could come from palm oil waste: biochar, biooil and fertilizer.

“I think the response was very good. But the obstacle is how to commercialize the products, that is the difficult part,” Dr. Norazana says.

“It starts with building the first plant. You need a lot of effort and you need a lot of support, and then you need a lot of capital from the government. If you depend on the university alone, you cannot go anywhere,” she says.

To convince the industry she needs to expand her research from lab scale to pilot scale, so products can be demonstrated on an industrial level. This is the only that way, the industry will be interested in investments in waste energy plants, Dr. Norazana claims.

“It’s not easy to transform from scale to scale. A lot of unexpected incidences can happen, and you need to face certain challenges to troubleshoot when you transfer from small scale to pilot scale. The university can provide the fundamentals. But in order to commercialize, you need capital: you need governmental support,” she says.

She has hope that continuous collaboration with Scandinavian countries can help the process.

“I do have relationship with Sweden and Denmark, because they already started with this technology, and it shows that you can do this. Provided the financing and that the government support us“.

A golden opportunity

The first year in Denmark the couple struggled due to lack of allowances which made it hard to cover living expenses (after a year, the allowances was revised to cover them both). And as anybody who travels overseas knows, it takes a lot of energy to understand the systems and the behavior of a foreign culture. Dr. Norazana had to delay her registration at the university, to wait for her kid could be enrolled in a kindergarten. And her first experiments did not go well, and she had to repeat them.

“The first year was quite heavy. I almost gave up and wanted to go back to Malaysia. But after that everything became good. I could give more efforts to my studies and still have more time with my family. As long as you complete eight hours a day on average, you can decide when to work. The work ethics is based on trust, and I think that is very important,” Dr. Norazana says.

Today she is grateful that the government supported her and her husband’s stay at a university abroad, and calls it a golden opportunity. She is more than ready to pay back for that investment, and to help her country to develop rural areas.

“I have to give whatever knowledge I got from Denmark back to our society,” Dr. Norazana affirms with a determined smile.

Berit Viuf is a Danish science journalist; the interview was conducted during a reporting trip to Malaysia and Thailand