A young Danish literature researcher is reading novels and poems from the Caribbean archipelago in order to understand the relationship between colonial history and environmental degradation.

Literature is always mirroring the society around it. Sometimes this mirror even influences the course of the society in which it’s written and read.

”As an academic, I believe that cultural objects play a crucial role in the way we conceive the world. I am interested in how literature can change perceptions and how an academic devotion to a literary tradition such as the Caribbean, can contribute to a new outlook on our connection with the physical world”, says Anne-Sophie Bogetoft Mortensen, a Danish PhD-researcher from RUC, Roskilde University.

From her busy reading desk at Roskilde University or at home in Copenhagen, over the last couple of years she has been exploring the junction between colonialism and climate crisis in three centuries of Caribbean literature, primarily poetry. But before she could dive into the literature, she had to first familiarize herself with the language and poetic models of the region.

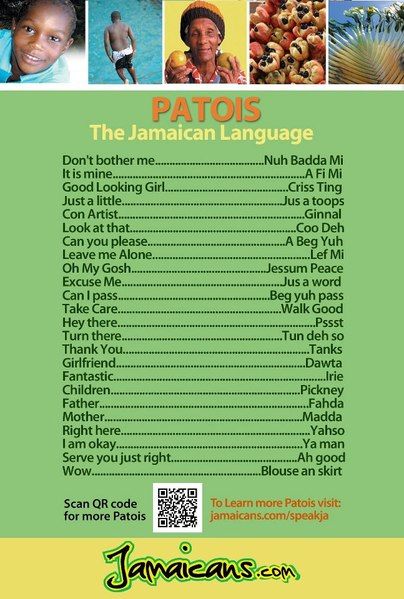

”Language and colonial history is profoundly intertwined in the Caribbean”, Anne-Sophie explains. ”British English, which is the official language of the islands’ literature I work with, expresses a British reality. The pace, the symbolism, the rhythm, mirrors a typical British landscape with green hills, heavy rain and grazing sheep. Some of the most significant Caribbean literature theorists argue that these British rhythms and poetic models are unable to reflect fully the very different experience of living in the Caribbean with its history of earthquakes, recurring hurricanes etc. It simply does not have the capacity to captivate and express those experiences.”

”Rhythm is very important in the Caribbean poetry. Now, when I say rhythm, I am referring to rhythm in a given text, but also to as rhythm which is conditioned of the physical materiality around the writer”.

”Tides have a specific rhythm, waves have a specific rhythm, and the hurricanes which hit the Caribbean archipelago every other year have yet another rhythm. These natural phenomenona and their rhythms are reflected in the poerty, and so one could say, that there is a rhythm imbedded the landscape, and that this rhythm is reflected in the poetic landscape of the texts that I read”.

The starting point for Anne-Sophie’s keen interest in Caribbean literature was her worries about the current threats towards the colonized countries, societies and landscapes from global warming.

”I am interested in how literature can change people’s mindset and how a serious study of a literary tradition, as in my case the Caribbean, possibly can inspire a new perception or attentiveness to the connection between human beings and the physical world around us. The literary texts are my primary empirical material, but I am approaching it in a very interdisciplinary way, connecting it with theories from critical geography, history and non-western philosophy from around the world”.

”To many people, the climate crisis might seem like a new thing, something that is just flaring up now, but many climate historicist will argue, that our current climate crisis began back in 1492 with the start of colonization, with the transportation and exploitation of humans, plants and land.

This recognition might create a higher degree of global cohesion. If many of us have become a little bit immune towards all the news stories about global warming, economic growth, racism and other controversial issues, art and culture might possibly create some sort of new and much needed resonance”.

An outsider’s viewpoint

Early in her research process, Anne-Sophie made a deliberate choice not to try to contact the writers whose works she is studying. It’s the texts that are the objects of her interest, not the intentions of the artists behind.

Of course, she planned from the beginning to go to Barbados, Jamaica and other islands on to get a sense of the literary environment, and to participate in literary events and engage with local scholars, but because of the Covid-19 pandemic and the resulting closed borders, that hasn’t been possible – so in spite of many years’ interest in the literature from the place, Anne-Sophie has actually never been to the Caribbean in her life. The object of study is squarely the texts in front of her.

”I would not call it a handicap – but it has definitely been a challenge for me”, she says.

At the same time, the corona restrictions have in a paradoxical way been a help for Anne-Sophie in her studies. She has been able to participate in a lot of online international conferences, PhD-courses, reading groups etc., which would normally not have been possible, as everything took place online. Therefore, her primary collaborators have been researchers around the world, rather than other researchers from Danish universities:

”If I could start over again, that is one of the things I would have done differently. I would have reached out more to relevant people at RUC and other Danish universities, rather than being so focused on international networks. It just happened that I very quickly got into online contact with some highly recognized international literature professors and an international group of critical geographers who helped me a lot”.

”So in many ways, corona has been a blessing in disguise for me. There is a broad international community of researchers in my field, and because everything has taken place online, I have been able to participate in much more than I would otherwise have been”.

Language is in itself a challenge in the region. Many of the local authors in islands such as Barbados, have written about the difficulties of writing about the Caribbean environment, history, culture etc., in a language that is originally the colonizers. Many of the authors are searching to install their own national language, to achieve something which is a language in itself and not just a dialect of somebody else’s language.

”Most of the authors and literature-theorists in the islands grew up speaking English with their parents, but is a local variant of English. Jamaican English is not the same as Barbados English, or Bajan as the locals would call it, and both are very different from British English, which is what the locals were taught in school. The literature of the various islands mirrors these variants of written English, and because of that they are indeed quite challenging for someone like me to read, let alone analyze. But this also means, that I am much more aware of small language details, and that I am constantly attuning myself to the Caribbean reality, via the language”.

Anne-Sophie recognize that the curriculum at literature studies at most Danish universities have become less ”white” during the last ten to fifteen years. The students are expected to read more and more non-western literature, both fiction and theory.

”However, the whole literary community both in and outside of the university is still very dominated by the West here in Denmark. I wanted to write a PhD about something else in order to challenge myself”.

Coasts and plantations

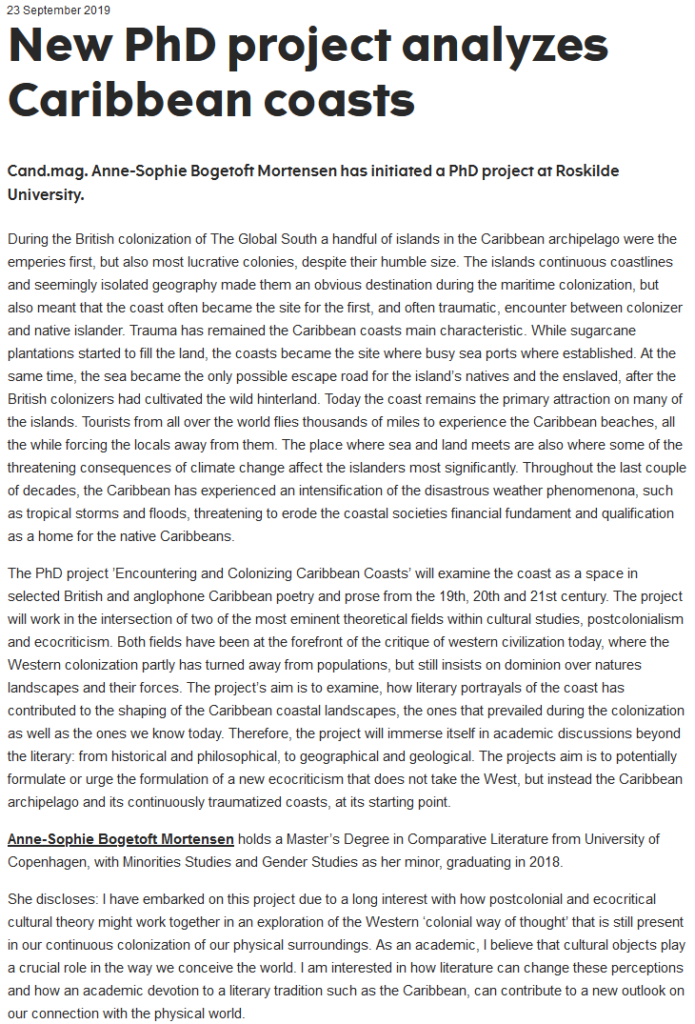

In the beginning of her research, Anne-Sophie focused on the shore as the main theme of her dissertation. She observed the Caribbean coast as a literary landscape.

”The islands’ continuous shorelines and seemingly isolated geography made them an obvious destination during the maritime colonization, but also meant that the shore often became the site for the first, and often traumatic, encounter between colonizer and native islander. Trauma has remained the Caribbean shore’s main characteristic”, she explains.

”The shore were at the same time symbols of the beginning of the nightmare – and the only possible escape. They became the site where busy sea ports where established. At the same time, the sea became the only possible escape road for the island’s natives and the enslaved… Today the shore remains the primary attraction on many of the islands. Tourists from all over the world flies thousands of miles to experience the Caribbean beaches, all the while forcing the locals away from them”.

”The place where sea and land meets are also where some of the threatening consequences of climate change affect the islanders most significantly. Throughout the last couple of decades, the Caribbean has experienced an intensification of the disastrous weather phenomenona, such as tropical storms and floods, threatening to erode the coastal societies financial fundament and qualification as a home for the native Caribbeans”.

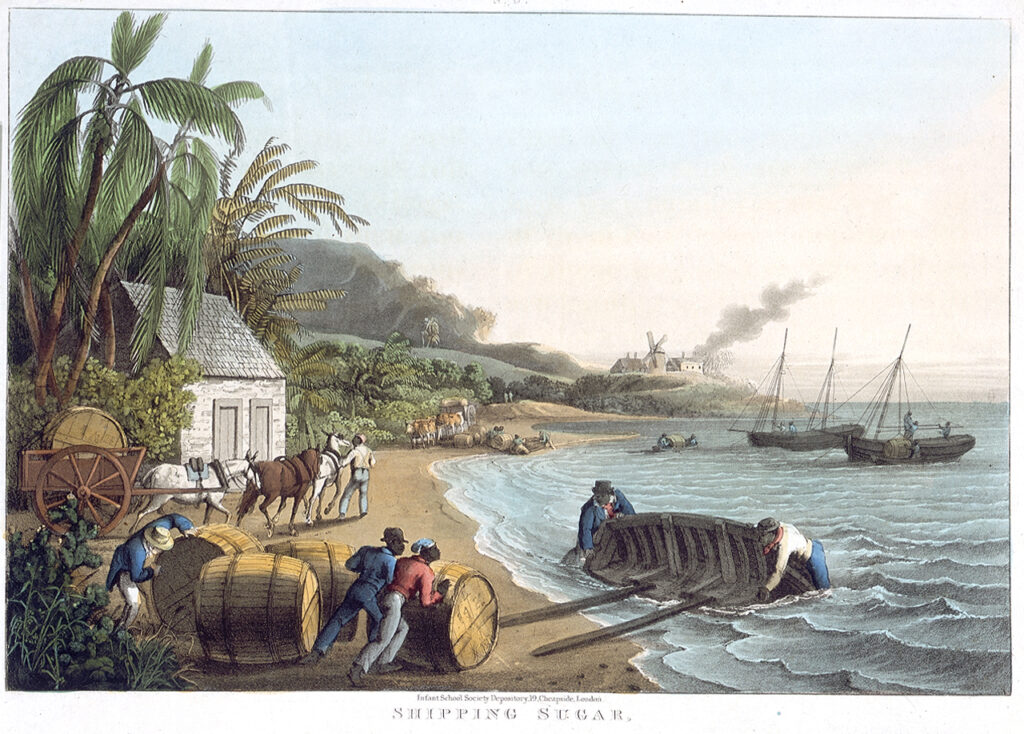

But gradually through the research process, this original focus on the shore was supplemented by a broader view, as the inland plantations began playing a major role.

”The Caribbeans have often been presented as a kind of rest area on the enslaved peoples’ tortuous travel from the African continent to the American continent, but actually there were a lot of sugarcane and cotton plantations on the islands themselves. Much of the suffering took place there, and much of the literature has its roots there, in that tumultuous and tormented soil”, Anne-Sophie explains.

“The plantations were a result of an extractivist way of thinking: in the plantations both soil, plants and humans where being treated as nothing other than resources fit for making profit off on.”

”Something happens to those who are enslaved under such conditions. A kind of alienation. They are put there as a work force, and the only relation they have to the soil they are cultivating and the only relation they have to the land they live on is that they are working it, draining it, in order to give all the crop to their masters. That certainly does not create ground for taking good care of the land.”

”Neither the cotton nor the sugarcane became part of the enslavedes identity in a positive way. In the literature, both of those crops are often closely connected with pain.”

”In contrast, on some of the islands, the plantation owners gave the enslaved and their families small private plots, often with bad soil, that they were allowed to cultivate themselves. Not out of pity of course, but because it was expensive to feed a work force of 30 families. Better they took care of that themselves”.

”They were able to sell small amounts of these private crops and exchange them with other families. It gave a limited feeling of independence, but the purpose was to keep the enslaved families in check. The plantation owners were very much afraid of any form of rebellion”.

”On these private plots, many families were growing yam, a root vegetable which they had originally brought with them from their African homeland. While cotton and sugar became symbols of repression, yam became a small symbol of reclaiming one’s freedom, trying to create something for oneself”, explains Anne-Sophie Bogetoft Mortensen.