India’s economic growth story is remarkable: from a less than $500 billion economy at the turn of the millennium to the world’s third-largest economy with over $3.5 trillion in 2022. The GDP per capita increased from $451 to $2,379. As the country’s economy boomed, there has also been an increase in waste generation. In 2000, India generated 115,000 tonnes of waste per day which has now risen to over 150,000 tonnes per day.

Although the amount of waste generated per day increased by a modest 30% since 2000, many Indian cities are struggling to cope with the burden of unprocessed waste. This is despite India having one of the lowest per capita waste generation rates at just 0.57 kilograms per capita per day. In contrast, countries like Denmark and Germany, often lauded for their waste management practices, generate 2.17kg and 1.72kg of waste per capita per day, according to the World Bank Group’s What a Waste 2.0 – A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050 report.

One of the primary waste management challenges in India is the low levels of waste segregation at the source – the practice of sorting waste into different categories at home.

Waste Management Landscape in India

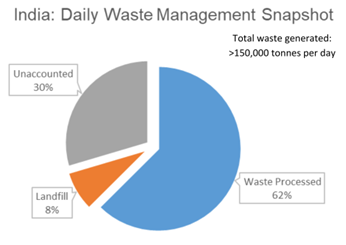

As of 2022, India’s capacity for treating solid waste stood at 95,000 tonnes per day, which accounted for 62% of the total daily waste generated, based on data provided by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB). However, the remaining 38% (approximately 55,000 tonnes per day) of waste remains unprocessed. Out of this, about 8% or 12,000 tonnes per day finds its way into landfills. What happens to the remaining 30% – around 45,000 tonnes? Unfortunately it lacks documentation.

It is presumed that a significant portion of this unaccounted waste is either carelessly discarded in the environment or managed within the extensive yet disorganized waste management sector. This sector engages millions of individuals working as waste pickers and scrap dealers. Their primary tasks involve gathering waste from landfills, openly disposed garbage sites, and households. Subsequently, they sort the collected waste into categories such as plastic, e-waste, and other segments to prepare it for further processing. Although there are no official figures regarding the precise number of waste pickers in India, estimates from over a decade ago by the Alliance of Indian Waste Pickers pegged it at approximately 1.5 million individuals.

Mountains of Waste

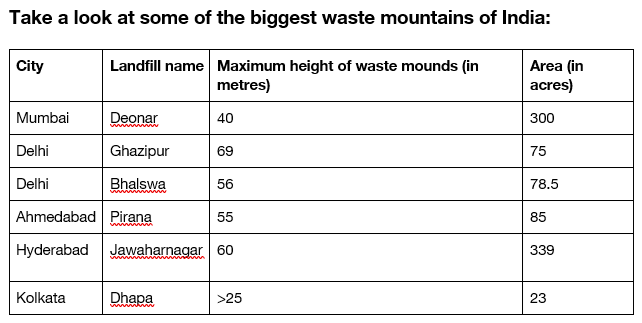

India’s daily waste management capacity increased from just 21,000 tonnes per day in 2015, to 95,000 tonnes per day in 2022. However, most cities and towns in India have huge landfills with millions of tonnes of waste, accumulated over the decades.

According to CPCB data, over 87 million tonnes of waste is piled up at 1,356 dumping sites across India. At 453 of these sites, approximately 48,000 tonnes of waste continue to be dumped every day even now. Only at 255 of these sites have government agencies initiated biomining and bioremediation measures to reduce the accumulated waste and restore the environment.

In many of these waste landfills, the waste accumulated over the years is causing environmental problems, including pollution of groundwater and soil, harmful environmental conditions for people living in surrounding areas, and degradation of the air quality. There are often reports of fires at these dumping sites due to the inflammable gases released by the heaps of rotting waste.

Waste Segregation Woes

At the core of India’s solid waste management challenges lies the lack of segregation of waste at its source – the sorting of waste at home into recyclables, non-recyclables, and biodegradables.

The rules governing solid waste management in India were first introduced in 2000 and were subsequently revised as the Solid Waste Management Rules in 2016. These make it mandatory for every waste generator to segregate waste at the source. However, the enforcement of these rules varies significantly across India’s 28 states and eight union territories.

According to the CPCB, 100% segregation of waste at source occurs in only one state and union territory each. In the remaining regions, the level of segregation varies widely, from a complete lack of segregation in some cities to partial coverage in others.

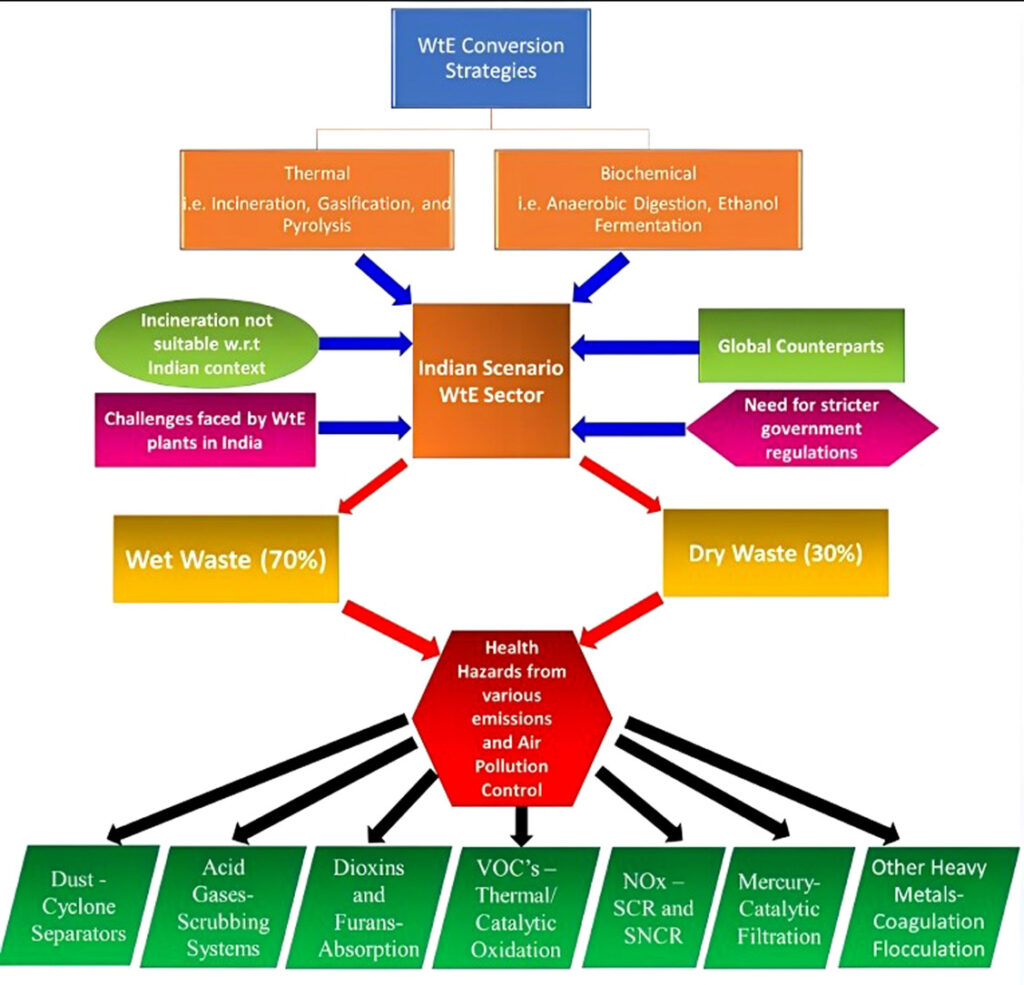

The lack of segregation at the source has also hindered efforts to convert waste into energy, despite India’s substantial potential in this area.

According to India’s Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, the potential for Waste-to-Energy (WtE) generation in India exceeds 5,000 MW. However, only 11 waste-to-energy plants are currently generating 132.1MW of energy by processing 11,000 tonnes of waste per day although the installed capacity of WtE power plants in India is around 550 MW.

A major hindrance is the unseggregated nature of waste collected from households. A study published this year in the journal Environmental Technology & Innovation points out: “To operate the waste-to-energy plants effectively, the waste has to be collected and segregated according to the requirements of the plant. India lacks the proper waste management standards that are necessary for proper functioning and continuous supply of quality feedstock required for WtE plants.”

Success Stories: Smaller Cities Take The Lead

Some Indian cities have taken the lead in waste management, serving as inspiring examples of how waste segregation at home is the first step toward a landfill-free city. Most of these cities are smaller cities where the municipalities are more enthusiastic and flexible, and suffer less bureaucratic apathy and political interference as compared to big cities. For context, there are more than 40 cities in India with million-plus population.

Panaji

One of these cities is Panaji in the state of Goa, a small city with a population of around 120,000. Panaji achieved landfill-free status despite generating around 42 tonnes of waste daily. The city’s commitment to waste management included the implementation of a revolutionary plan in 2021, which saw waste segregated at the source into 16 categories, now expanded to 28 categories.

Ambikapur

Another landfill-free city is Ambikapur in the state of Chattisgarh, with a population of over 150,000. Before 2015, Ambikapur had a stinking and overflowing landfill, but it has since transformed this site into a beautiful garden. This change was made possible through the city’s municipal body and self-employed women’s groups, who embarked on a journey to achieve 100 percent segregation, collection, and processing of waste. While waste is sorted at home into recyclables and biodegradables, further sorting occurs in more than 150 categories at the Solid and Liquid Resource Management (SLRM) centres.

Indore

Indore, located in the state of Madhya Pradesh, is often hailed as the leader in waste management and cleanliness in India. It is also an exception to the rule, with a population of around 3.5 million. It has been ranked as the cleanest city in India for six consecutive years by the government in its annual cleanliness rankings. Since 2016, the city has ensured 100% segregation of waste at the source. In 2019, the city’s municipal body removed a landfill that had accumulated 1.5 million tonnes of waste over decades through bioremediation.

India’s Quiet Success in Plastic Recycling

When it comes to recycling plastic waste, there is a story that often goes untold. Denmark is known for its strong environmental initiatives. The country recycles more than 70% of the waste it generates. However, a closer look reveals that Denmark faces challenges in recycling plastics.

According to the Denmark’s ‘Action Plan for Circular Economy’, in 2019, the country managed to collect only 25% of the 514,000 tonnes of plastic waste it generated. Estimates suggest that only half of this collected plastic waste was recycled. This equates to a recycling rate of just 12.5% for plastic waste in Denmark. As part of the policy, by the year 2030 Denmark looks to reduce its plastic waste incineration by 80 percent.

In contrast, India recycled 27% of the plastic waste it generated in 2020-2021, according to the compliance report by the CPCB on the implementation of Plastic Waste Management Rules. Considering that the nation generated an estimated 4.1 million tonnes of plastic waste during that period, approximately 1.1 million tonnes were recycled. Remarkably, five of India’s 28 states recycle more than 50% of the plastic waste they produce.

Pursuing Shared Ambitions and Collaborative Initiatives

While Denmark advances its efforts towards establishing a successful circular economy and sustainable waste management practices, India is equally committed to enhancing its waste management strategies.

At the national level, India’s commitment to addressing the waste challenge is underscored by the ‘Waste to Wealth’ initiative – one of the nine scientific missions overseen by the Indian government’s Principal Scientific Adviser. This mission is dedicated to the identification, development, and deployment of technologies for waste processing, energy generation, material recycling, and the extraction of valuable resources.

India’s waste generation is projected to increase by 4% annually. The India Investment Grid reveals investment prospects worth a staggering $2 billion in the solid waste management domain. Circular economy plays an important role in the India-Denmark Green Strategic Partnership. With the presence of abundant business opportunities in this sector in India, there is a promising outlook for collaborative endeavours between the two countries.

Nilesh Vijaykumar has a M.Sc. Science and Communications, Savitribai Phule Pune University, India. In September 2022, Nilesh relocated to Vejle, Denmark, and is a DDRN correspondent.