The human security framework was first introduced by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in their 1994 Human Development Report, seeking a more people-focused understanding of security. In 2011, a Human Security master’s programme was started at Aarhus University as the first of its kind. Aiming for an interdisciplinary and holistic approach, the programme is directed by the Department of Anthropology in collaboration with the faculties of Natural Sciences and Technical Sciences. I sat down for a chat with the coordinator of the programme and associate professor of Human Security and Anthropology at Aarhus University, Christian B. N. Gade.

From state-centred to human-centred security

Until the end of the Cold War, security studies were mostly focused on state and military security. However, during the 1980s, a debate emerged about how narrow or wide the security concept should be as some scholars argued for including economic, environmental, and health challenges. This wider understanding of security lays the foundation for human security. Because human security is not a concept that holds one clear definition, it can be hard to grasp at first. I ask Gade how he would explain the framework: “The basic idea is that instead of focusing on the security of states, we should rather focus on the security of human beings, also because the mere fact that the state is secured in today’s world doesn’t necessarily imply that the human beings who are living within the states are also secure,” Gade begins. “It’s a very holistic framework saying that in order for human beings to be secure, there’s a need for freedom from want, and it’s also about freedom from fear and about a life in dignity.”

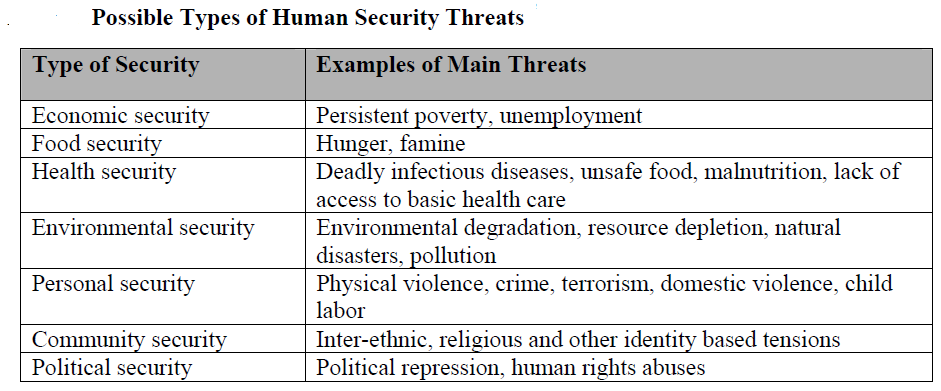

The UNDP divides human security into seven dimensions: economic, food, health, environmental, personal, community, and political security. However, all the dimensions are interconnected. “Quite often you’ll see a spill-over effect. Take, for instance, what is going on in Ukraine at the moment; of course the war is about personal security and violence and people suffering from that, but what is happening also has effects in many other dimensions. It has huge economic effects, it affects food security, it might have environmental implications,” Gade explains. “If we really want to make human beings secure today, we can’t just focus on violence. For instance, we need to understand how various dimensions are interconnected, and also how different parts of the world are connected,” he elaborates. This connection is illustrated in Gade’s own research.

Denmark and Uganda: Two ways to challenge punishment and justice narratives

Gade is doing two research projects at the moment, one in Denmark, and one in northern Uganda, that are both focusing on conflict management. Previously, Gade was part of a project about land conflicts and trust issues after the Ugandan civil war. He is now going to follow the reparations process after the trial of Dominic Ongwen, a former Brigade Commander in the Ugandan guerrilla group “Lord’s Resistance Army” (LRA). In February 2021, Ongwen was found guilty by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for a total of 61 war crimes and crimes against humanity.

“One of the critiques of the court [ICC] has been that it represents a form of distant justice too far away from the local victims. The ICC got funding from the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs to do a project where the outreach team tried to bring the trial closer to the local victims by means of screenings – video screenings – of trial proceedings in the local villages. They also facilitated dialogue meetings and so on, and I was hired by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to do an impact assessment of that project. I finished that last year, and now I’ll be doing this follow-up project where we want to follow the reparations process,” Gade explains.

“What we can see from the impact assessment is that the local victims really appreciated the involvement and the access they got. They were actually really satisfied, but what we could also see in the data was that because of the increased awareness, expectations in regard to reparations had gone up…the local victims started to expect more, and, in addition, we could see some local tensions or disagreements in regard to who should receive reparations,” Gade says. He thinks it is important to explore the long-term effects of the increased local access. Thus, the project will explore whether the victims’ expectations are met and follow the development of the local tensions.

In Denmark, Gade is one of the principal investigators (PIs) of a project together with the Danish police, where they work with restorative justice through the Danish victim-offender mediation (VOM) programme. “We are comparing the effects of victim-offender mediation with the effects of what is called restorative justice conferences. Basically, we are comparing two different ways of facilitating meetings between victims and offenders,” Gade explains.

One of Gade’s primary arguments in his research is that the idea of a dichotomy between restorative justice and punishment is problematic: “Restorative justice has been presented as a radically new justice paradigm that has been claimed to be radically different from punishment, but what I’m arguing in my research is that we might actually see these meetings as an alternative kind of punishment. When the offender is faced with the victim and other people he or she has hurt, that is often really tough for the offender,” Gade argues, adding that restorative justice might potentially be a more constructive form of punishment, as it has shown positive effects on recidivism, victim wellbeing, and economic costs.

He then demonstrates the holistic perspective of human security by relating his research in Denmark to his project in Uganda. “In a way, the research I’m doing in Uganda is also about this relationship between punishment and restorative justice, because some of the activities the ICC has used to bring the court process closer to the local victims are quite similar to the processes from the field we know as restorative justice,” he explains. “So I think, even though Denmark and Uganda sound very different, and are very different, the topics I focus on are really sort of the same in the two contexts.”

Potential pitfalls of human security

While a lot of interesting contributions are coming from human security, there are also scholars who are more critical towards the framework, arguing that it is too vague, that it’s interventionist or ethnocentric, or that it is “securitizing” political matters. I ask Gade about his opinion on these critiques.

“I think it’s always important to be critical, and that’s also true regarding the human security framework. One of the main critiques has been that the framework is too broad, it’s too holistic, and, due to this broadness, it’s difficult to operationalize. I actually don’t buy that critique, I would say,” Gade begins. “I think it’s essential that the framework is broad because the security issues that we are faced with in today’s world, they are just complicated. I think it’s a matter of fact that different issues are interconnected, and if we really want to understand the nuances and the complexities of the world we’re living in, then we need a framework that can deal with that complexity,” he reflects.

“Then, the framework has also been criticised for being a Western framework. It’s actually the same critique we have seen in relation to the concept of human rights”, Gade continues, before pausing to think for a while. “I think that’s a difficult critique in many ways,” he admits, before flipping the question around: “What do you think about it, Iselin?”

As a student of human security this feels like the moment I have been awaiting and fearing at the same time. I laugh nervously, before explaining that I think it is important to acknowledge that, as someone who is trained in a Western context, I will always have that bias with me. However, a strength of human security is that it looks at individuals in different contexts, and, moreover, places responsibility on the West for causing or contributing to many security issues that are affecting people in other places of the world.

“I completely agree, and I think, of course you might argue that the framework was born in a Western context, but that doesn’t mean that the framework doesn’t make sense to people in other parts of the world,” Gade responds. He elaborates with an anecdote from his own PhD research, in which he worked on the South African Truth and Reconciliation process after Apartheid.

“My focus was on something called ubuntu, which is an African philosophy about interconnectedness that was sort of used as a rationale for the way they dealt with the crimes of the past in South Africa, and I think that…the ideas about interconnectedness that are represented by ubuntu are also something I can relate to, to a wide extent, though I am not from Africa. As a matter of fact, I think these ideas about interconnectedness are quite similar to some of the ideas about interconnectedness that you see in the UNDP human security framework,” he reflects.

“But of course, if you want to work with this framework, no matter where you work with it, I think local ownership is important. You need to ensure that the framework you use makes sense to people in the local context,” Gade emphasises.

He adds that the framework should not be used as a tool for intervention, underlining that this is an issue related to potential political misuse: “I think it’s a fair critique to say that there is a risk of securitization to some extent, meaning that there is a risk that some people will frame something as a security issue in order to gain something politically. So there’s definitely a political dimension to the framework as well, and I think the best thing you can do is to be aware of that.”

I ask Gade how he keeps this awareness in mind in his own research. Again, he emphasises local involvement. For instance, they made sure that one of the participating PhD-student’s supervisors is from Gulu in Northern Uganda. “When I did the impact assessment for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, we – me and my local field assistant – travelled around to have meetings in different villages where we discussed the design of the project, the survey we wanted to do…how we could design a project that was meaningful to them and a project that they could actually use for something. And we’re going to do the exact same thing when we finalise the design of the new project,” Gade says. “But I think for me, it’s always a challenge how to design these projects in the best possible way.”

Why do we need human security?

Another strength of human security, according to Gade, is its interdisciplinary approach: “I really think we need competencies from different fields if we want to work with this sort of holistic approach to security in a meaningful way,” he states. This is largely reflected in the study programme. Gade’s background is in philosophy, and other lecturers have backgrounds in anthropology, biology, history, development studies, and agroecology. This results in a range of different research coming from the department, for instance on state-society dynamics and transnational issues in borderland regions, environmental issues in relation to the Anthropocene, and international criminal justice.

The programme has evolved a lot since its beginning, for instance, the teaching style, which now involves a lot of discussion and interactive exercises. Developing a good social environment has also been a priority for Gade. To him, the academic and social environments are two sides of the same coin and are also brought together through a student committee. Gade believes that a high level of student ownership is essential to foster ambitious and motivated students. For the future, he hopes that the positive development of the programme will continue. In a world threatened by conflicts, polarisation, and environmental catastrophes, this seems like a reasonable wish. The world is certainly in need of people who can navigate complex and interconnected issues from different perspectives, keeping a focus on the individuals standing in the midst of it all.

Iselin Møller Fredriksen is a Master student in Human Security at Aarhus University and DDRN university intern