Enlisting the Public

The universality of the themes covered by the SDGs speaks to the fact that there is not only space, but also interest, for the public to participate in the work towards the SDGs; contributions “through the involvement of everybody, not just the usual suspects like the government organisations or the research bodies”, as put by Dr. Mohammad Gharesifard, assistent professor of Citizen Science at the University of Groningen.

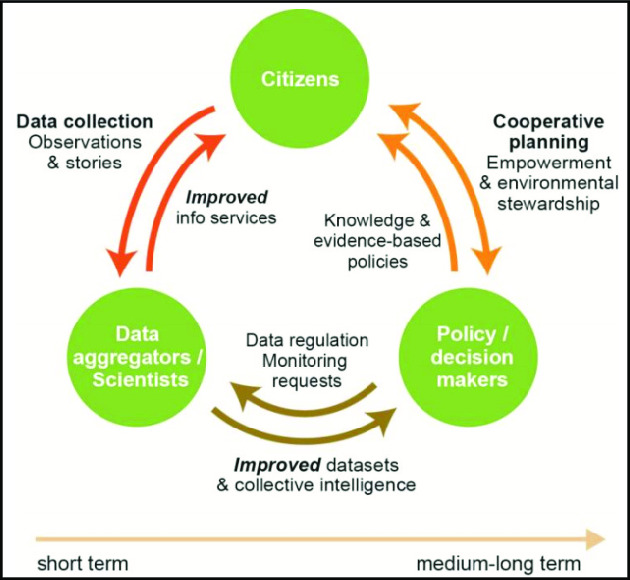

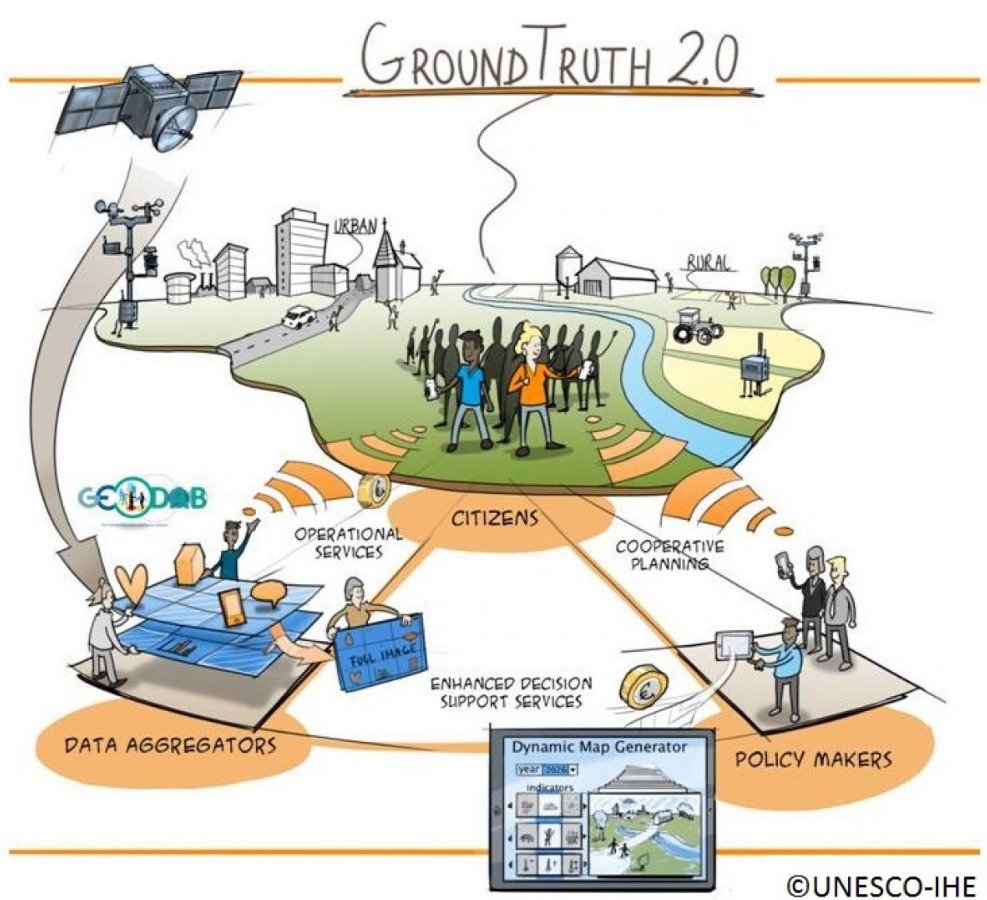

Citizen Science (CS), a mode of public engagement where members of the public actively participate in the research process, has been gathering momentum in recent decades, as a promising approach towards democratising science; an inclusive way to escape from the elitism of which science is so often accused. Due to their empowering potential, multiple CS projects have sprung up, such as the Ground Truth 2.0 project, in which Dr. Gharesifard was directly involved. The project, which operated in six different countries, aimed at establishing ‘citizen observatories’; networks of stakeholders (including members of the community) using technology and sharing information to monitor their environment. The project constitutes just one of the many examples of citizen science.

Such initiatives equip interested members of the public with tools and knowledge to play their part in (natural/social) science research, for instance by collecting data. The themes of such projects also tend to revolve around issues that affect the citizens, ranging from tracking biodiversity, and monitoring air and water quality, to public involvement in setting the agenda for urban development projects. Looking at the foci of CS projects, one notices that they are not simply topics of abstract research; they tend to be pertinent issues related to the environment around the participating citizens. The link between the themes of CS projects and sustainable development issues is strong, and these themes often overlap with those of the SDGs.

Grassroots Data

In the spirit of substantive action and evidence-based practice, numerous indicators exist for each of the 17 SDGs to monitor progress and evaluate the work towards achieving them. A substantial and consistent flow of data is, naturally, necessary for making informed assessments towards these indicators.

But generating and collecting such a large set of data is not easy, especially when this monumental task is formally allocated exclusively to certain organisations. Organisations such as governments and national statistics offices are relied upon to be the sole ‘pump’ through which the necessary stream of data flows. This is a substantial demand, and these sources are proving to be insufficient.

Their inadequacy seems to necessitate that new, non-traditional data sources be utilised, as argued in a study on the interface of CS and the SDGs, and CS initiatives perfectly fit that niche. In the words of Dr. Gharesifard, “with citizen science you actually have a complementary source of information to measure the SDGs. So that is one of the beauties of citizen science; in parts where we have a lack of data, we can perhaps cover it.”

However, this raises an important consideration: How to strike the right balance between taking advantage of CS data towards the SDGs, while keeping the official bodies accountable for fulfilling their obligation of effective and accurate tracking of the progress towards the SDGs.

Currently, CS projects are already contributing to some of those goals, with the potential to contribute to even more. In total, such initiatives can contribute to up to one third of all the different indicators that are used to demonstrate progress towards the various SDGs, as per a 2020 paper mapping CS contributions. These contributions are heavily put in service of ‘monitoring’ the SDGs – checking the progress against the different indicators – but the potential for contribution extends to achieving them as well: “We can discuss the SDGs and citizen science in this dichotomy of monitoring and achieving”, says Dr. Gharesifard.

Crossing Continents

While the citizens involved are often local to the area, the relevance of the issues they tackle can be global. And even if the individual cases are area-specific, the objective of citizen science – the involvement of the public – can find its place across borders. It is no surprise then that many CS projects involve collaborations between multiple countries across continents.

Ground Truth 2.0 was such an example; a 3-year project running from 2016 to 2019 that set up and studied six citizen observatories, including two in Africa (Kenya and Zambia). “The idea was to really co-create these citizen observatories; not to go there with a tool that is already developed, but with a blank canvas, if you will, and start with bringing all the stakeholders around the table to first discuss the issues and only then come up with tools or solutions for how to tackle these issues with public participation through citizen science”, says Dr. Gharesifard, who was involved in the project, specifically referring to the Kenyan case.

However, the canvas with which the team arrived in Kenya was not completely blank. Since the area where the observatory was to be set up was near the Maasai Mara National Reserve, Dr. Gharesifard and the team thought “ok, perfect case for biodiversity monitoring. We go there and we develop an app, perhaps, that tourists can use when they go on these safaris to basically count animals […] so we can have a better count of the state of biodiversity in this reserve”.

They started by organising a session bringing stakeholders together; representatives from the county and the national government, the University of Maasai Mara, and local citizens. A diverse sample of stakeholders, but not representative since, as Dr. Gharesifard admits: “We couldn’t engage everybody, only those who could speak English, so it was not really a representative sample. But we tried to engage a very diverse group and we did our best.”

“The session started and we tabled the idea” he recounts. “The county government was actually very much in favour of the idea, they really liked it. But the local people actually started telling us that this is not the full picture. They explained that, although conservation of the animals in the national reserve is an important focus, it ties to more pertinent issues; some of these animals, such as lions and leopards, can often wander off the reserve and attack grazing herds, on which many members of the community depend for their livelihoods. The message was clear: ´the more important thing for us is our livelihoods and not counting animals´.”

With the priorities of the citizens clearer, the theme of the project changed and evolved to include the information that the community was actually interested in. Dr. Gharesifard explains that they had to “refocus the idea on basically a balance between conservation and livelihood management”. “So, besides what type of animals you see [and] whether you see a case of conflict that you can report”, he continues, “they could share various information about water sources that they could take the cattle to, or perhaps better pastures outside of the conserved areas. And also things like prices for cattle etc.”

Finally, he adds one further major change to their initial idea: They completely dropped the idea of focusing on the engagement of tourists “because we realised that there are more important stakeholders to engage at the moment”. The next step was to develop the necessary tools to carry out the project. The team, researchers and citizens, started to work on co-creating an app where people could submit and share all this information.

The combination of crowdsourcing information that interests the local community, along with the fact that they all have access to this repository, allows such projects to contribute to goals of sustainability: Information on clean sources of water ties to SDG 6, monitoring animal conflicts ties with SDG 15, and so on. “In that sense, it [the project] could really promote sustainability through practice and through providing tools.” A very interesting outcome of the citizen monitoring of the conflicts between the animals of the reserve and their herd animals, is that it could also assist in safeguarding the security of their livelihood by providing evidence in support of claims for compensation; “this is a big issue, the local government is hesitant with paying compensation in these types of conflicts.”

Shaky Sustainability

It sounds ideal: Science being done in service of the public, while including them in all stages of the design, aligning with their priorities, and all that while also contributing to, and gathering data in service of, global goals of sustainability. But, of course, it is not that simple.

Citizen science projects are often touted as cost-effective sources of data. This notion is challenged in a study, co-authored by Dr. Gharesifard and based on the Ground Truth 2.0 project, where the authors conclude that “the cost of obtaining citizen science data is not as low as frequently stated in literature.” He adds that “you spend a lot of money and time on meeting each other, creating things together, thinking together, but after that when you have this and everybody trusts it and they start using it, then the cost goes down.”

But even these comparatively small maintenance costs can often be prohibitive for the sustainability of the project, with a common issue amongst CS initiatives being that they do not survive in the long term. Dr. Gharesifard expands on this topic by explaining that the issue is not the size of the funding per se, but rather its longevity: “A problem that we have faced a lot in citizen science projects is that there is a source of money, and with this source you can do a lot of things, but after the funding is finished the researcher is on his or her own way […] I think it’s a big flaw in the way that we fund this type of projects”.

He further adds that “you can do capacity building, you can try to train people also on doing these things, but still, this needs to be built into the design of the project, and beyond that, it would need to be built into the current ways of funding projects.”

A project may start with a lump sum large enough for its operation, but as soon as the funding is over, the financial responsibility is suddenly shifted onto the local stakeholders, making it difficult to keep up. A scheme whereby a portion of the funding is reserved for long-term maintenance and running of the project may be what is needed to ensure its sustainability; allowing projects to mature, so that they can eventually be run exclusively on local funds.

Context Matters

But overall, the most important aspect, which is at the heart of citizen science, is inclusion; hearing the voices of those whose lives are intimately intertwined with the issues at hand, and doing so in a genuine way. It is easy for a group of researchers – or an affluent country leading a CS project, for that matter – to approach with the assumption that they are leading. The importance of keeping this potential imbalance in mind is further underscored by Dr. Gharesifard when he says that “power dynamics [are] very important. Quite often we assume that when you bring people to the table they have the same type of authority or power and that’s almost never the case.”

He further elaborates on this in his 2019 paper, also drawing from the Ground Truth 2.0 project, about how ‘Context Matters’. As he later remarked, “There are countless ways of engaging citizens in citizen science projects […] it needs to match the budget, it needs to match the aim, it needs to match the time-frame, the available resources, and other realities on the ground. The context.”

After all, isn’t context what it ultimately is about? Local citizens getting involved, setting the agenda, having a voice, lest the context is ignored. In the words of Dr. Gharesifard, “Context matters; it really is an issue of thinking carefully on what makes sense and what is possible”, and getting the context right is the first step to defining a problem and coming up with a realistic response; a sustainable solution.

Christos Vlasakidis is a M.Sc. student, Science Education and Communication, University of Groningen, Netherlands, and DDRN university intern.