African footballers have always enthralled the English Premier League fans, but have you ever thought of the hardships that they had to endure to reach up to that stage. Football is not just a sport for the youth in Africa but a way for them to escape poverty. As the founder of the Mbete Youth Football Project, Buster Emil Kirchner shares his experience coaching the rural youth in Mbete, Zambia. Born and raised in Esbjerg in western Denmark, Buster has been into development work for some years now. He had volunteered for several NGOs across Africa, mostly offering football coaching for rural youth in the continent. He’s also into sports journalism and works as a freelance journalist for a couple of newspapers in Denmark.

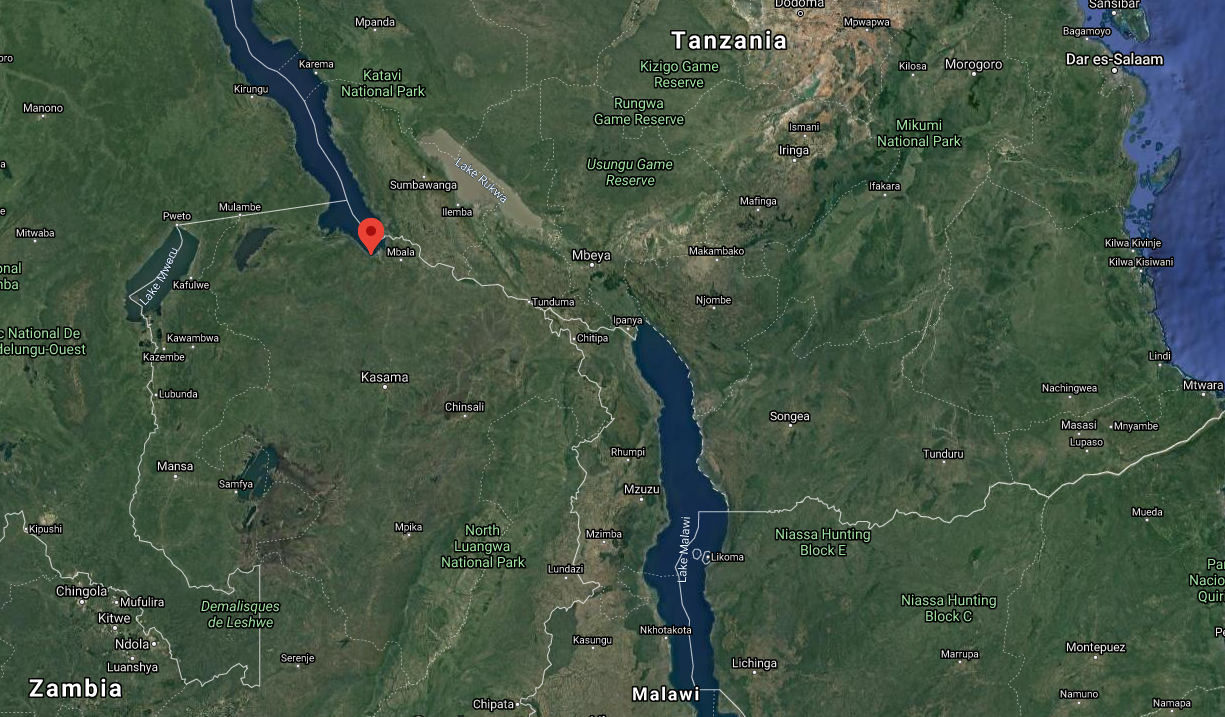

Buster is currently in the final year of his bachelor’s in religious science at the University of Copenhagen. Just as I interview him on Zoom, he’s back from Tanzania, where he was on an exchange to learn Kiswahili. As a student of religious science, Buster had many reasons to do an exchange in Tanzania. First, Kiswahili, the language that he chose to learn in the final semester is one of the most spoken languages in Sub-Saharan Africa. Learning Kiswahili would help him communicate with the people of Mbete, where his NGO is based, as it borders to Tanzania and the folks share many things in common. Moreover, Kiswahili is a lingua franca, i.e., it is a common language adopted by two different groups of people who spoke distinct dialects. Having done his exchange in Zanzibar, Buster was fortunate enough to explore the long colonial history of the region and how it shaped their culture. In religious science, Buster does learn anthropology, sociology, post-colonial developmental theories, etc., and it has helped him broaden his perspectives about life in Africa.

As his final year includes an exchange, he is supposed to write a long essay on religious scriptures. For this, Buster must analyze one of the holy scriptures, modern-day newspaper articles, or poems in the language that he chose to undertake. When asked about his dissertation, Buster says, ‘’This would probably be my dissertation’’.

Fascinated by the people and their culture, Buster made his first visit to Zambia as a volunteer for Eventure Zambia in his early 20’s right after high school. His first experience in the country etched in him a feeling that the youngsters in the village don’t have anything to do in their leisure time. Given the poor condition of schools in the village, the teenagers were neither encouraged to go to school or even if they did, they dropped out at some point. Drawing on his coaching experience from a young age, Buster got to approach some of the local players and offered them training. Further meetings with the local team players, coaches, and committee members got the ball rolling for the Mbete Youth Football Project in September 2017. The project had been offering three training sessions a week and has formed three teams: one below 10 years of age, one below 14, and one team below 17.

The project currently runs using foreign aid, but Buster is determined to make it self-sufficient in the future. Having said that, Buster is aware of its vulnerability due to lack of funds, and the financial situation of Zambia is not conducive for the development of sports.

Three years from starting the project in 2017, Buster has been pivotal in developing strategies for running the project till 2025. Their mission is to make the players self-sufficient and to motivate them to take up better jobs in the future. The project encourages the players not to drop out of school, driving them to secure better livelihoods. In the coming years, Buster has plans to organize computer classes for his team members and may get into community farming to fund the NGO. As he looks for more innovative methods to raise funds, he is in some way trying to inculcate an entrepreneurial spirit among the youth.

Why Mbete?

Mbete is in the northern province, which he feels is one of the most neglected zones in Zambia. For the youngsters of Mbete, attending professional football coaching is impracticable as most of the training is offered in far-off places,16 -20 hours by drive. Having stayed in Mbete for eight months during his stint as a volunteer for Eventure Zambia, Buster is known to the people there and used to their culture as well. If he were to start the project elsewhere, he should be investing a lot of time researching about the place. Also, Eventure Zambia is just around, and therefore, he could approach them anytime for help. He’s also known to the coaches there, and therefore, he could seek their help in organizing training sessions. Over the last three years, Buster has recruited 12 Danish volunteers to coach the rural youth in Zambia.

Buster wants to end what you call the ‘dependence syndrome’, i.e. depending on someone for each and everything. He feels this dependence syndrome has been, and still is, a vital element in understanding development and foreign aid. Buster, therefore, wants to cultivate an entrepreneurial spirit in the players and to motivate them to earn better jobs for a living. He always motivates them to play matches outside their home village. The players meet their expenses themselves, for which Buster encourages them to work in the early days before the match. ‘’Once they have the drive, the players will find some means to raise money for their travel, gears, etc.’’, says Buster.

Buster believes the boys won’t learn anything if he’s to sponsor them all the time. ‘’Once you encourage them to make an effort to raise what they can, that’s when creativity, pride, and ownership is accomplished’’, says Buster. Furthermore, football gives the players opportunities to travel outside their hometown to get attached to professional teams. The project also offers interactive workshops on self-employment, family planning, how to prevent drug abuse, STDs, etc. For this, Buster takes help from some of the local NGOs in the nearest town. Being a student, Buster can’t make himself available for all the workshops, but he does follow up on them.

Responding to my question on the importance of sports for the betterment of rural youth, Buster uses football as a metaphor for achieving higher goals in life.’’ When you have a ball, everyone will follow that ball. I’m not the one controlling the ball, it is just there as a phenomenon. If you take it to school, kids will follow it to school. If you take it to a profession, they will follow it to get into that profession’’, says Buster. Football is so powerful in motivating people, and Buster considers it as a platform for the youth to achieve a better future. Playing football is also reflected in their character as Buster finds the youth more disciplined, dedicated, and motivated as they get along with the training.

The anti-colonial independence movements in Africa had witnessed football taking a central role especially in countries like Ghana, where its former president Kwame Nkrumah organized football matches to resist the colonial supremacy. ‘’It is still a medium of freedom and joy’’, says Buster.

He also has experience coaching in Sierra Leone, where he volunteered for Football for A New Tomorrow. From his experience in Africa, he feels the children there don’t have a fair chance to get into professional sports. Furthermore, football has a commercial side, and a lot of businesses are centered around football. Most of the major clubs in the Zambian Super League are based in the two big cities of Lusaka and Ndola. Lack of resources in the northern province makes the rural youth feel left out of the sport. For them, getting exposed to professional football means a lot of money.

Sports development in Zambia

‘’Sports in Zambia needs a better structure and a better organization’’, says Buster. He is currently in talks with the Football Association of Zambia to develop a better structure for youth football in the country. At the moment, the chances of rural youth to get exposed to organized football are meagre, and even if they do, their salaries would be far lower than that of their counterparts in the western world.

Moreover, football is a platform that could help achieve some of the SDGs. Playing football, or any sport involving some kind of physical activity for that matter, helps you stay healthy. Though Buster, nor his NGO, could address the problem of malnutrition in Mbete, their activities are in a way helping the rural youth to uplift from poverty. Also, his NGO is trying its bit to promote quality education and encourages the team members to continue schooling.

Responding to my question on how serious is the Zambian government in promoting sports and its development in the country, Buster says, ‘’They are over-ambitious but too short of funds to achieve them’’. The Zambian Football Association has great plans for the way forward, but the limited funds leave them far from reaching their goals. Though it’s not all about money, he feels the association can do much more by capitalizing on the budding talents. Buster would suggest prioritizing football in the country, perhaps, under the Ministry of Health as it has got something to do with the good health and well-being of its citizens. He would encourage not just the youth but even the middle-aged folks to play football as it could prevent them from turning obese. Though he’s critical of the government, he also accepts the truth that the ministry itself is under huge pressure. Apart from the corruption allegations, unprecedented challenges in the form of new epidemics like the COVID19 has further left them with newer setbacks. Also, Zambia is nearing state bankruptcy, and countries like China are taking over many of its internal areas as its debts pile up. If Zambia is to declare itself bankrupt, that is likely to leave the future of its folks at stake.

‘African way of coaching’

As a foreigner, Buster had many challenges to run the project. One of the main challenges was to set up a structure for the project, especially the rules, by taking into account the cultural differences. Growing up in Denmark, Buster couldn’t accept the coaches beating the players with a stick for their mistakes. He could only relate it with human rights violations, but it was nothing for a Zambian coach who had never heard of these rights. Beating kids is something common in Africa, and the coaches believe that’s how they should make them disciplined. ‘’That’s the African way of coaching’’, replies Buster to my question on how he coped with their system. Buster even had discussions with the local coach, where he decried his act of punishing the players. Perhaps, it could be Buster’s presence that made the kids, who are otherwise used to punishments, disobey their coach leading to him stepping down. ‘’The world is not as black and white as we think’’ says Buster. Though he condemns such actions, instances like this prove our cultural differences.

Buster also believes that sports can reduce inequalities in many ways. Moreover, his NGO is doing its bit to provide quality football training to people who otherwise cannot even dream of it. Also, he’s critical of the western world for funding corrupt and broken states that misuse the bilateral foreign aid for non-humanitarian things. With people like Buster trying to find the hidden talents in rural Africa, we can expect to see more African players finding their way to international football soon.

Krishnanunni Mavinkal Ravindran has a MSc in Sustainable Tropical Forestry, University of Copenhagen

SUPPORT DDRN SCIENCE JOURNALISM. DONATE DKK 20 OR MORE (APPLICABLE IN DENMARK ONLY)

(APPLICABLE IN DENMARK ONLY)

![]()

![]()

Krishnanunni Mavinkal Ravindran

Krishnanunni Mavinkal Ravindran