If you are interested in international relations and development, you have probably come across the terms: Global South and Global North. Chances are you are using them without a second thought. But have you ever asked yourself how we came to use these terms so easily? And are they not misleading in today’s world?

Let’s discuss this, and a little bit more with Helen Balslev Clausen, Associate Professor at the Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities at Aalborg University, campus in Copenhagen.

Helene is very active in doing research and participating in projects with countries in Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East, focusing on entrepreneurship to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). One of the most recent highlights of her work in progress is a publication, Handbook of Sustainability Transitions and Innovation in Latin America, which is coming out in the next 6 months.

What is the handbook about?

“It’s mainly focused on local movements in the sense of how all these localized initiatives can actually upscale, so we can learn something about it on the national level, on the global level instead of only maintaining them at a local level. The huge sustainable transitions need to come from below, as well as being guided through policy.

A part of this handbook will be about innovations in Latin America, but the publisher asked us to expand the view because it was so nice. So, other parts will include Bangladesh, Myanmar, and Africa – East Africa.”

Do you mean a bottom-up approach, but also a top-down?

“Yes. It needs to be a mix, but mostly from the bottom up because the people’s needs and voices need to be heard, and depending on context, we cannot do the same, even though our governments think that we can do the same all over. Context is extremely important.”

Can you give an example of one of these initiatives?

“For instance, there’s a part about waste management and garbage workers. In Argentina, they develop their own system and machines, and they try to recycle plastic bottles in a more efficient way. The garbage workers collect the bottles and divide them into groups. Depending on the plastic, some will be made into new products to sell.”

In 2021, the Ministry of Public Space and Urban Hygiene in Argentina received four separate awards for their innovative initiatives in recycling and waste management.

“It’s quite interesting how they have this knowledge about the plastic that our engineers at universities also have, but they can also figure out how to separate and decide on which plastic is recyclable and not. I think that’s impressive. They’re also doing it in Kenya because there’s a huge plastic problem,” adds Helene. “I think we need to be more alert to what’s happening at the local level and look at the different context.”

The origins of the term “Global South” in a nutshell

Other terms have been used previously to represent power and economic differences between nations: “First, Second, and Third World”. These terms depicted world powers starting with the US, then the Soviet Union, and lastly the “developing” countries. The term “Global South” was used for the first time by American political activist and writer Carl Oglesby in 1969, observing the culmination of the North’s dominance over the global South after the Vietnam War. The term refers to economically disadvantaged nation-states and has been used primarily within intergovernmental development organizations that originated in the Non-Aligned Movement.

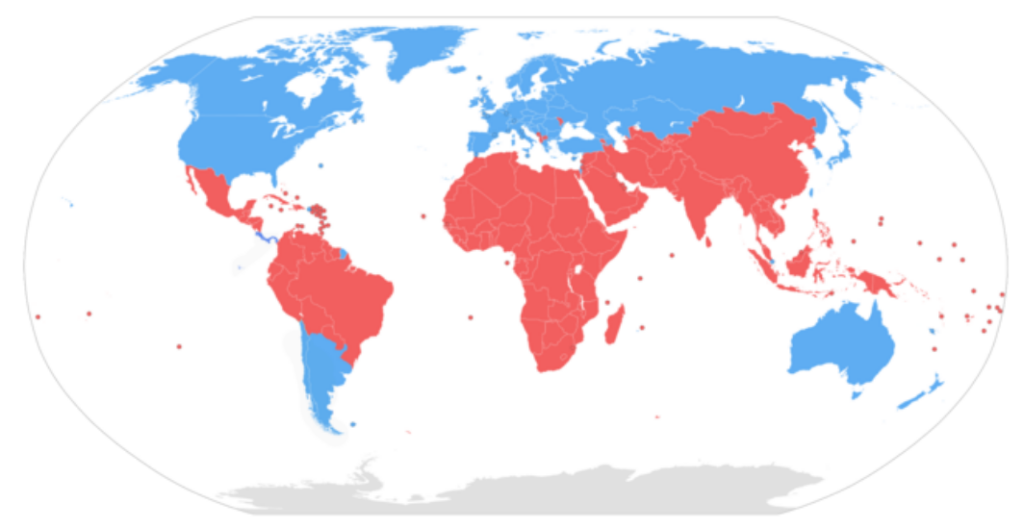

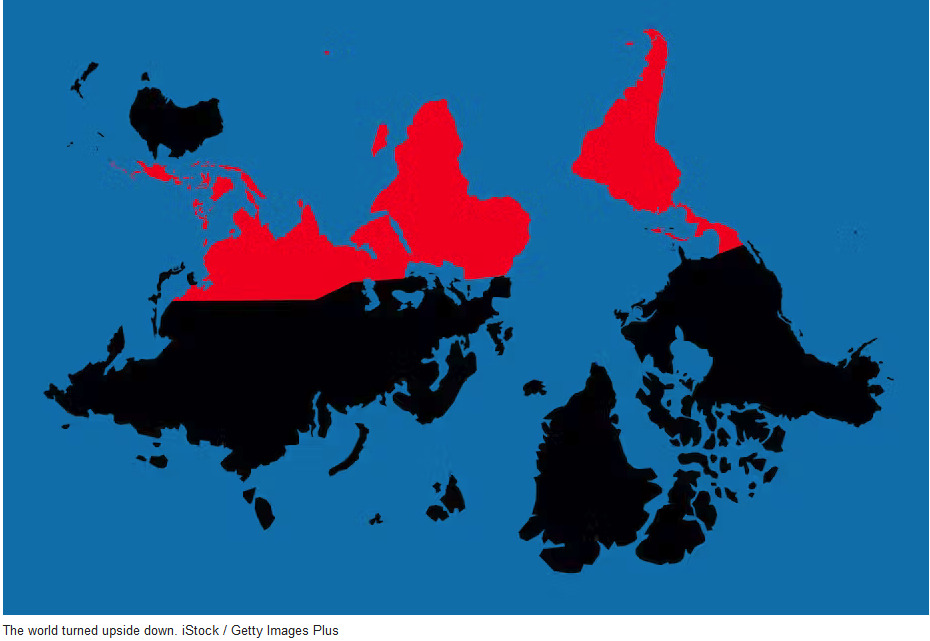

However, the term was not really used widely until the 1980s, when the Brandt report introduced an imaginary boundary dividing the world into the Global North and Global South. The main criterion for the Brandt line was gross domestic product (GDP), dividing the countries between those with a higher and lower GDP per capita. Most countries with a high GDP were located in the Northern Hemisphere, however, it is important to understand that the term is not geographical, but geopolitical. In fact, India and China, countries considered part of the Global South, are located in the Northern Hemisphere, while “Northern” Australia lies in the South. The division based on economic growth becomes even less relevant nowadays, as many Global South countries are gradually becoming economically stronger, especially the BRICS countries.

Do you think it is okay that we use the terms Global South and Global North?

“I think it’s very problematic that we use these terms, and I don’t think we should characterize the Global South and Global North in that way because it follows a lot of stereotypes and images. Even though these terms are more neutral, or objective, which I think is better compared to the terms ‘developed’ and ‘developing’, or a ‘Third World’ – but I’m not too keen on this divide because you see a lot of interaction between Global South – Global South and you see a lot of it is not homogeneous. Neither is the Global North. Just within the European Union, you can see huge differences between the countries. I don’t think it’s very useful to talk about this divide either. We can talk about trade relations, we can talk about identities and transnationality, development as such, but I think it’s very problematic to use Global South and Global North as a term.”

“And usually, there are also, unfortunately, a lot of connotations to who is the most clever, who is the one that has the best education, who is the one that is coming with resources… That’s a lot of associations that are not very constructive in the long term and even less when we talk about sustainable development goals,” says Helene. “You can see the narrative about the Global North – we think it’s us having the resources to create transitions, and that’s sort of the image. But if you move around all over Africa, Asia, and not least China and India, you see how they are making a lot of progress related to the SDGs. They’re spending a lot more resources than we are in the Global North. We keep on doing what we have always done, we don’t really create interventions that are necessary to reach the global agenda.

But still, we maintain this weird, I think very weird, narrative about Denmark being very green and sustainable. That’s not the case. We could do a lot more.”

Another project Helene is working on now is about coffee flowers in Uganda. The collaboration between Danish and Ugandan researchers focuses on how to use not only the beans but the whole plant. “It’s very interesting what they’re doing, and they are extremely inspiring to work with,” she comments.

Around 10,000 small-scale farmers in Uganda are participating in workshops where they’re trying to partly educate the farmers but also figure out together how the coffee plant can be used differently and how farmers can benefit from it in a more sustainable way. However, there is much to learn from them, as Helene states: “We are working with agriculture in Denmark and different agronomists in Uganda and with a lot of stakeholders to set up the value chain for these farmers. But they have a lot of knowledge, so we want to co-create everything with them. So, it’s not only research, but also about creating a new value chain where these farmers, mainly female farmers, can benefit from their knowledge and capture the value of their own products and innovate.”

If you want to learn more about this project, check it out here: Coffee flowers – turning waste into value with female farmers and socio-tech solutions.

Based on your experience – do you think that countries generally considered part of the Global South need help from other countries in terms of development and doing business?

“I think we need the private sector to create transitions… Countries in the Global South are very keen on entrepreneurship, and they know how to do it. They have been doing it for a long time, for many that’s a way of survival as well. So, they set up their businesses to survive because they don’t have the same welfare system as we have in Denmark, for instance, or countries in the Nordics.

So, I’m not sure. I don’t think they need aid as such. I think they need to, from my experience at least, when I enter into collaboration with them, they are keener on knowledge. Different knowledge is how they can create value and maintain value. But we also have to remember that we are within a global system where trade is important, and the conditions adjust. Both socially, but certainly also economically. The economic system is extremely unfair. And it might be too rude to say exploitation, but there are some conditions that could be renegotiated.”

Can you elaborate on that?

“Let’s take certifications and labeling systems, for example. It’s still the Global North countries that are deciding the conditions for the farmers and it is extremely expensive for the farmers in the Global South to enter this fair-trade system.

The farmers simply cannot afford to be a member of a fair trade. Their conditions are actually sustainable, but they need to verify documentation and fulfill a lot of processes and requirements that are too expensive apart from paying to be part of the organization. So, all these systems that we set up all the time to control our consumers in the Global North might come in handy for the consumer but for the farmers in this specific case, I think we must reconsider.”

So there needs to be better conditions for collaboration?

“Yes, more just conditions designing. For instance, value chains that are more socially and economically just.

We can see a few companies in Denmark, such as Kontra Coffee and Husted Vin, that are actually skipping fair-trade and saying: ‘no, we know our farmers, we know they are sustainable, they cultivate and do the best they can, and they are sustainable because they cannot afford pesticides. So, we’ll just negotiate and talk with them directly’. This way the value actually stays with them.

There is a recent movement to reject these systems that are set up, where we still sort of capitalize on people that we shouldn’t. It’s extremely important as well that this movement is going on in Denmark.

We also have to take care and look into what we’re actually buying or doing because some are also greenwashing and simply using the SDGs as a way to basically sell more and capitalize on sustainability, instead of actually doing something or acting upon it.”

“And of course, the private sector needs to create profit, but we also have to take care of not only going there, sort of capitalizing on everything. Fortunately, we have private stakeholders that are also looking into the social part of their business model, so they integrate the sustainable and social part and it’s not only about profit.

We need to rethink our business models. I think the biggest challenge is to include the social part.

Some of the businesses I know are trying to change, but it’s also extremely difficult because the guidelines and the policies in, among other countries, Denmark, are not encouraging it. Quite the contrary. So, we also need the politicians to speed up, move faster.”

Read more about Helene’s experience with research collaboration and policymakers in the Global South in an upcoming article.

Petra Kascakova is a M.Sc. student in Culture, Communication and Globalization, Aalborg University Denmark, and a DDRN Intern