Climate change is one of the main challenges that humanity faces around the world today. And women being half of the world’s population have been taking this crisis really seriously, especially in Chile, one of the countries that generates the most garbage per person in the South American region.

According to data from the Ministry of the Environment (MMA) of Chile, every Chilean produces 1.26 kilos of waste per day. This metric means that 8.1 million tons per year are discarded in Chilean landfills. “The relationship that we have with the environment has been not only one of use, but also one of abuse”, states Claudio Cerda, an academic at the University of Chile, whose specialty is urban anthropology. He explains that Chilean modern society’s way of consumption involves “magically” getting rid of our waste. “Over the years and with the development of cities, we have become accustomed -particularly in certain more privileged areas- to a kind of consumption behaviour where what we consume, we throw it away assuming that this waste will magically disappear.”

Cerda continues: “Most of the people of Chilean society have developed this type of behaviour. We have not generated a reflection on our relationship with waste. Therefore, everyone that tries to build a different perspective on these habits collides with these big walls of cultural tradition”.

The role of women in the circular economy in Chile

Women in Chile have been experiencing this backlash because, despite our consumption behaviour, there is a “circular economy” ecosystem growing in the last decade mostly composed of women.

“They get involved through practice because they apply their projects and actions in their own local territories. Their actions are directly related to care work and the sustainability of life”, explains Daniela Frias, urban planner and geographer who has worked on the implementation of public policies in this area. “In this scenario, it must be understood that in the current context of the climate crisis, women are the first victims of the damage caused to the environment. So of course women have a perspective on how to act at the moment of some catastrophe or some risk in this climate crisis”, adds Frias.

Something similar thought Pamela Bravo, when years ago she read an article about permaculture. She was fascinated but also concerned about climate change. “As soon as the opportunity arose, I decided to make recycling organic matter the basis of my business,” she remembers. “At that time, I used to live in an old apartment in downtown Santiago, so on a small balcony I began to recycle organic matter”.

Her concern became a service and since 2009, the main mission of Compostera.cl (her business) has been to deliver tools and knowledge to people in order to reduce their carbon footprint. In these fourteen years, Pamela Bravo has created two podcasts (8 seasons), an Instagram account with 19.4 thousand followers, and YouTube channel with a platform where she teaches 4 online courses at affordable prices.

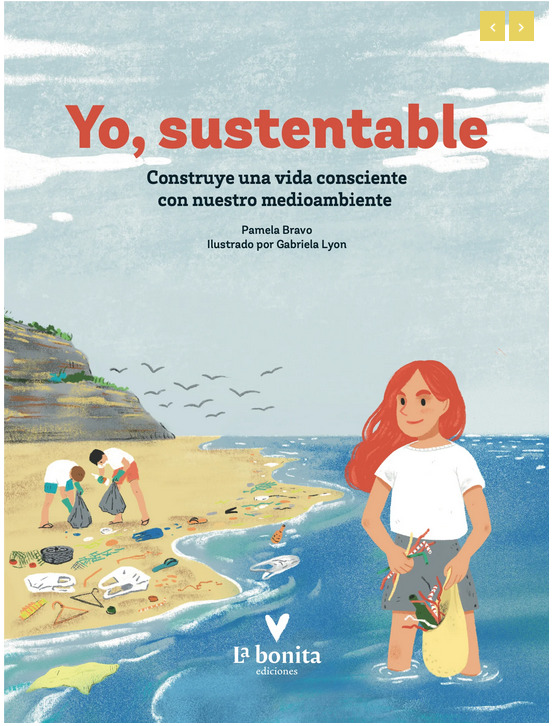

Adding to this labour, she makes talks and consultancies. She also published a book titled “Yo Sustentable”. In this book ”Plá” an 11-year-old girl shows the reader different ways to take care of the planet and lead a more sustainable life. To this year 9,000 copies of this book have been printed and later this year the adventures of “Pla” will arrive in Korea.

“The need for environmental education is so big that it is almost impossible to cover it. I hope everyone can be educated to be sustainable in different areas. When you engage with certain groups especially in sustainable culture you might start to think that there are a lot of people interested in taking care of the planet, but in reality, there are a lot of people that must be educated on these issues”, Pamela points out.

Regarding the role that women play in the circular economy cycle, Pamela states that in her experience, women play an important one: “I have participated in several organisations, volunteering, and I realize that more or less 90% of the sustainability ventures or micro-enterprises belong to women”.

“There can be many reasons,” she explains. “From the connection with the earth and the care of the planet to the fact that women assume a maternal role. For example, I am currently participating in the “Fundación Basura” where at least 80% of the participants are women. I am a volunteer in an urban garden and sometimes one or two men appear, but the majority are women”.

For Macarena Gajardo, Executive director of Fundación Basura – an NGO aimed at protecting the health of the planet, reducing waste, and mentoring policymakers, women have been historically in charge of care work. “Therefore, we have great power in our hands. From taking care of our own home, keeping it clean, deciding what things we buy, and taking charge of the culture of caring for our family. This also applies on a macro level”, explains.

“There are also ecofeminist movements that link the relationship and empathy that women feel to the “Mother Earth”. So the role of women today is fundamental but step by step, this role is being extended to people in general, since everyone can contribute”, adds Gajardo.

Pamela Bravo from “La Compostera”, also highlights that even though the participation of women is bigger in this area, their efforts are not as visible when it comes to being in the spotlight. “Women recycle organics and produce organic food, but when men get involved, they are ´entrepreneurs and ´CEO´ in the world of recycling”, she criticizes.

Chiloé, the road to a greener island

In the south of Chile, there is a large island called Chiloé known for its green mountains, wetlands and forests. In Chiloé, “the magic island”, it rains the majority of the year, and lots of Chileans visit during the summertime to enjoy the beautiful landscape and unique culture but in 2019, people from Chiloé demonstrated against the poor management of the waste in the island. Since then, a lot of women are working to have a greener island and transform the way they consume and live their everyday lives.

Lorena Bórquez is an example. She lives in Castro, the main city of Chiloé, and she turns cooking oil into soap. She began her business because of her own concern to protect nature and was inspired by the tradition that her mother and grandmother started: “I associate making soap with my childhood because my mother also made soap when I was a child, but with animal fat, as did my grandmother, who learned to make soap in Punta Arenas, the Chilean Patagonia.”

At first, when she first started making soap, Lorena, an agricultural engineer, was going through a career crisis after her maternity leave. This action transformed her life. Years ago, she was watching videos on the internet to make soap. Nowadays she trains and holds free workshops in various indigenous communities in southern Chile.

“I am happy to be able to train and teach people to make soap. I started doing this because as a professional I felt stuck. I wanted to work and feel useful. It’s true, I was at home with my family and all that, but as a professional, you want to be in your business. And this project allowed me to fill myself up and have that contact with people that is fascinating and also protect the environment. I am happy, this craft fills my soul”, she states.

Lorena also has a perspective on the role of women in building a more sustainable culture and her commitment to projects related to recycling. “In my case, I faced a domestic problem, and I didn’t know how to solve it and I think that many women are faced with similar conditions. In addition, we as women are always trying to save money. Somehow, we always end up moving to the domestic sphere no matter how educated or many degrees you have. You are the one who sees yourself facing the decision of what is thrown away in the house, what is useless. You always find yourself figuring out how certain objects can be repaired, among other issues. As a woman, you face these situations every day. It is a cultural thing, good or bad, I don’t know, but this definitely influences why we are more present in the circular economy ecosystem”, she states.

As a feminist and professional who works in the field, Daniela Frias states that in terms of public policies, a key issue to fight the climate crisis is to put care and life at the centre of our actions. “We must understand that care is not only about human beings but also about nature and local territories. This is a fundamental issue in order to build a social and ecological transformation, where women and nature are not relegated”.

She states that all the actions -regarding the climate crisis- that women carry out in their local territories, in their private or public life constitute an emancipatory praxis. She concludes: “Women build freedom and alternative paths to the capitalist system and that must be highlighted. We need to make these actions visible and invite all people: men, women, and people out of the system to get involved in caring for life because ultimately, women do have a leading role in this area but that means a greater burden for them. So a more harmonious relationship with nature as to take place not only in our family or communities but also in our local territories”.

The Chilean poet and Nobel Prize in Literature Gabriela Mistral wrote a beautiful poem named “The Pleasure of Serving” where she reminds us that serving others is not only a duty but also a source of immense happiness.

Through this poem, she encourages people to take on tasks that others may avoid and to find joy in small acts of service. Lots of women in Chile are taking actions that a lot of people avoid in order to promote a circular economy and reduce organic waste through various initiatives and businesses. This is their service. By doing so, they are not only helping to protect the environment but also creating economic opportunities and promoting social justice. Overall, women’s involvement in waste reduction and circular economy initiatives is crucial for achieving a more sustainable and equitable future in Chile. And as in the poem of Mistral, these actions, and the role they play in the circular economy left us wondering as Chilean society if we render our service today. “To whom? To a tree, to your friend, to your mother?”.

Marta Apablaza Riquelme is a freelance science journalist based in Santiago, Chile