Researchers from North and South are supporting each other in a Danish-supported network exploring how young people in West Africa navigate streams of information about security and other local matters in a new media landscape.

When researchers and reporters come from abroad to cover the complicated security situation in the deserts of Northwestern Africa, most of them have never been there before, and they seldom know the language.

They need local assistants and interpreters whenever they leave the capital cities and go into the field. Often, these assistants and interpreters know the discourse in the North and the researchers’ and reporters’ expectations too well, so the result is often reports about ethnic conflicts which confirm any prejudices about Africa that the news consumer in the North might have.

”By contrast, the local people we are cooperating with get their information from social media. They are going into the field in semi-bad vehicles, fighting their way through dangerous terrain. They are able to see a lot of insider nuances, which we normally don’t see from the outside,” Associate Professor Heidi Bojsen from Roskilde University (RUC) says. She is the key person in an international network of researchers who are exploring how young people in West Africa navigate streams of information in crises of security, health, and migration.

The network has active members from Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, as well as countries in the North, including Denmark. Recently, it received a grant of 1,2 million Danish kroner from The Independent Research Fund in Denmark, enabling members to meet for workshops and webinars in order to exchange experiences and observations. In January 2022, the first physical workshop took place in Ouagadougou, the capital of Burkina Faso.

The grant is not a research grant, but a network grant. The objective is to create an independent platform enabling sociologists, anthropologists, media and culture researchers, as well as media workers from the North and South to share knowledge and develop new theoretical and methodological tools to understand how media is being used and the role media play during complex crises in West Africa. The work is certainly not starting from scratch.

“The South partners were active long before we came into the picture,” Heidi Bojsen says. “We could observe that these people had real good expertise. A promising environment was developing in Ouagadougou in academic research, as well as critical journalism and communication. They had problems getting their publications digitalized and translated into English. We wanted to support making the results of their good work visible abroad.”

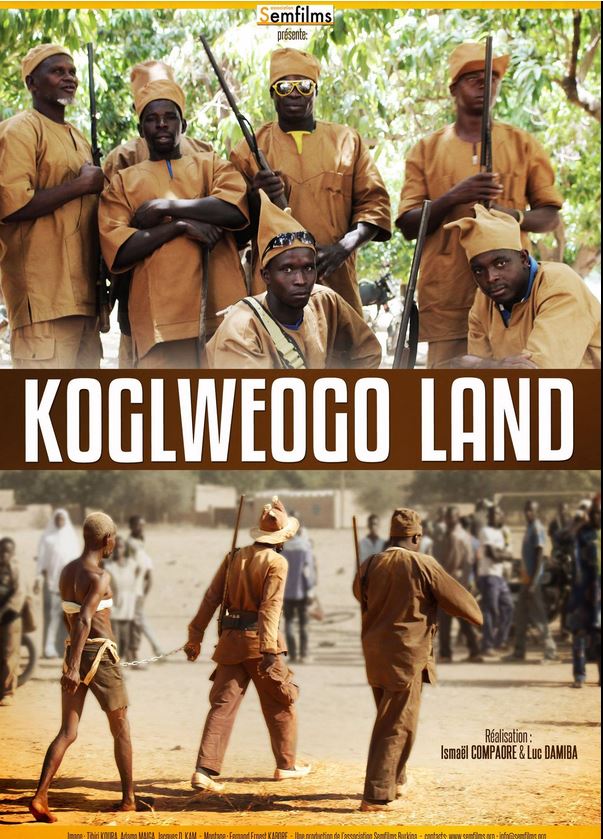

The network is initiated by Heidi Bojsen together with Ismaël Compaoré, a Burkinabe political scientist and prize-winning maker of documentary films.

”We contacted researchers in Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mali, and they decided to join the network, even before we had one Danish krone in financing. I have spent between six and eight years working towards understanding the local media debate and shaping a local network, entirely financed by myself and my allotted research time and money at Roskilde University. That’s why the local researchers trusted me, as well as they trusted Ismaël. They knew us.”

The Danish grant goes to flight tickets as well as expenses to accommodation and catering during the workshops. The money cannot be spent on fieldwork and research itself. Two webinars, each lasting two days, have already been held.

”The focus of the South partners is clearly the security situation in the three West African countries. They choose to look at how the security situation is mediated and controlled by a media ecology consisting of mainstream media as well as social media, especially in relation to young people. We have discussed methodical issues, like how we can verify information from the field when it’s too dangerous to go there for a long time? How do we protect our sources? How do we work with information gathered through groups on social media?”

Forwarding South Expertise to the World

The results of the work within the network is available here. Each member of the network will have their own blog, where they can write small updates about the security situation. Other fields of focus will be migration, health, and climate.

The group of researchers in Ouagadougou, centered around Ismaël Compaoré, have cooperated with Heidi Bojsen in her earlier projects, working as interpreters and assistants. The new network is built on a long-established cooperative relation.

”I have known Ismaël since he was a young active student advising people in danger of being thrown out of their homes about their legal rights. Later, he produced a few documentary films, one of them about semi-military groups, partly with support from Danish financing. He and his video crew dared to go into the field, mapping, interviewing and documenting these groups. They have gathered the biggest and broadest collection of empirical material on this issue.

“I was able to see that this material compared with other information was fabulous, much more varied – with many more nuances. It showed the diversity of the self-defense-groups. It showed how different they were. Western observers only went to the same few places where a gatekeeper was available, and where logistics were functioning well.

“I learned a lot from them,” Heidi Bojsen continues, ”and in return, I could offer them access to articles and books they would otherwise not be able to access. They learned an academic method from me. I told them about the theoretical debates within their field, so that they could begin analyzing their observations themselves. I could invite them to conferences and make them co-writers on academic papers. In short, I could offer them a route into an international research arena. Until then, they had only been operating in a local documentary arena in Burkina Faso. I had no ambitions to become an expert in these issues myself. My role was to forward their expertise to the world”.

This division of labor has been continued in the new and broader network. Already before the start of the network, this way of cooperating has resulted in several academic articles by Burkinabe members of the network in an American academic magazine. And in parallel with the workshops and webinars, a new department of journalism and media is being established at the University of Burkina Faso by members of the network.

”In Denmark, we are very good in the fields of water and health, and we have had military forces in Mali,” explains Heidi Bojsen. ”But we have no knowledge about how information is produced and distributed, and neither about how the population looks at us and our local counterparts. We operate in a bubble, because anthropological and critical media studies have been completely absent. We are driving along the express road, but we don’t see the other road users.”

A Specific Media Know-How

Compared with other countries in Africa, Burkina Faso and Niger have traditionally had a relatively free press and intellectual life. ”I don’t feel that the people we are cooperating with are afraid of saying something which they are not allowed to say,” says Heidi Bojsen.

But two years ago, a new law was passed in Burkina Faso, which forbids reporting about terrorist acts. The intention was to combat fake news and bad journalism. But the new law has definitely made it more difficult to research and report on these problems, according to Heidi Bojsen.

In this situation, social media provides a platform where truthful narratives of entrepreneurship, creativity, and social activism appear side by side with the temptations of illegal migration options. At the same time, the research team has already made the observation that many young people quickly learn to navigate shrewdly between the different media platforms.

Of course, it is still a major factor that access to smartphones and other tools to receive media content is very unequal. ”It is extremely expensive. People are helping each other to get access to social media,” Heidi Bojsen explains.

”Only a few in villages have a smartphone, and we are very interested in questions like: What happens to information in WhatsApp when it is mediated by another person, or when you only get a glimpse of it? How much do the illustrations influence the message, especially in relation to those who don’t read French? A specific media know-how is developed under such circumstances. It has to be local researchers who dig deep into this issue. They are the only ones who can really be part of it.”

So when the local researchers venture into the desert, according to Heidi Bojsen, they are able to better understand and describe that problems affecting security along major roads are much more diversified that just expressions of ethnic conflicts, as reported by many global media. Explaining these conflicts as ethnic strife is too simplistic. The reality is more complicated.

”It’s much more a question of other things, like misunderstandings and rivalries between traditional chiefs. Very few villages consist entirely of people from one specific ethnic group. Most villages are mixed, and conflicts within the community don’t follow ethnic lines.

”Ethnicity is something that we all have. It’s not a reason for attacking each other – but it is certainly something to make fun of. West Africans are making terrible fun of each others’ ethnic heritage – but in most cases, that is not the reason why the security situation is so bad as it is,” concludes Heidi Bojsen. Also read previous article: https://ddrn.dk/3505/