We have to adopt an intersectoral approach to safeguarding health, says an experienced Danish researcher who has done that for all his professional life.

To address the serious health problems of the world, the health sector has to work in close cooperation with other sectors in society. These are not stand-alone challenges for the health sector, neither in the South nor in the North. “The health of people should not only be the responsibility of the health sector”, says the Danish public health scientist Peter Furu, Associate Professor at the Global Health Section of the Department of Public Health at the University of Copenhagen and Head of Studies at the university’s Master of Disaster Management program. ”The responsibility for health has to be shared with other sectors in society as well”.

”Look at the transport and energy sectors and the indirect contribution to ill health among humans through uncontrolled pollution. Globally, around seven million people die every year because of the health impacts of outdoor or indoor air pollution. Activities related to transport and energy generation have major health implications – positive and negative. For the adverse effects it is often the health sector that pays the bill of the damage made. It is important to work together across sectors when addressing the cross-cutting determinants of health, whether of environmental or socio-economic nature”, Peter Furu explains.

Since its beginning in 2013, he has taken part in the ”Global Health” Master of Science program at the University of Copenhagen as an educator – together with colleagues from Anthropology, Natural Resource Studies, and Medicine. ”In this two-year master of science program, we take a multidisciplinary approach to learning and we focus on the need to cooperate across different sectors in order to solve global problems”.

Peter Furu has passed the official retirement age, but he is still active in a number of research projects and educational programs. After graduating in 1984, he spent most of his professional life as a consultant, researcher and educator at the Danish Bilharziasis Laboratory (DBL), a Danida supported sector research center, specializing in vector-borne tropical diseases and international health. DBL was established in 1964, then merged with the University of Copenhagen in 2007, and was finally phased out in 2012, together with two other Danida supported research institutions (Danida Forest Seed Centre and the Seed Pathology Institute for Developing Countries).

Over the years, Peter Furu has been deeply involved in efforts made in the context of the International Association for Impact Assessment (IAIA) and the World Health Organization (WHO) developing principles and guidelines for “Health Impact Assessment” (HIA). It is an assessment tool available for use in connection with new, major development initiatives ensuring that new activities do not result in unforeseen, adverse health problems and maximizing the potential positive health effects of those initiatives.

”It is known, for example, that hydropower projects, although generating many positive outcomes, may have tremendous negative health consequences. When the Aswan Dam in Egypt and the Akosombo Dam in Ghana were built in the 1960s, they resulted in serious epidemics because the dam reservoirs and new irrigation schemes provided breeding opportunities for disease vectors like freshwater snails and mosquitoes, and thousands of people were exposed to new infections in those countries. Today, we are better at predicting the negative health consequences and designing the projects in ways that will minimize these adverse effects”.

“Today, we have a set of global principles and practices for Health Impact Assessment, however, in most countries it is still not mandatory to perform HIAs. To safeguard health in relation to new development initiatives, ideally, the HIA practice should be equally ensured and mandatory as we experience, for the environmental impact assessments, now common and obligatory for major infrastructure projects in most countries”.

Research capacity development

Already as a student, Peter Furu had a strong wish to work with health, environment, and development issues.

Throughout many years at the Danish Bilharziasis Laboratory (DBL), his focus was mainly on schistosomiasis (bilharziasis) epidemiology and control, as well as other neglected tropical diseases. At the laboratory, medical doctors were working together with biologists and anthropologists. DBL was established as a research institution, but an important part of its purpose was to develop institutional and individual research capacity through training and supervision of doctors and other health staff and professional groups in the Global South.

“I was there for more than 30 years. We had many PhD and master’s students, primarily Africans, going through the system during my years at the laboratory”, Peter Furu remembers. “They did their field work in their home countries, and then they came here for a shorter or longer time for data analysis and writing and defending their thesis”.

He observed very positive developments during those decades.

“Generally, all the students from the South returned to their own countries. Some of them continued as researchers, others got important administrative positions at local health authorities or at universities, and knowledge and skills gained during their studies were considered highly relevant and useful for them in their respective careers”.

“There, they continued extending the capacity by sharing knowledge and skills with local colleagues. Thus, an institutional capacity development took place in the South parallel to the individual strengthening of research capacity. The aim was to raise local partner institutions to a higher level and also ensure they had proper laboratory facilities that made it possible for them to continue their work after returning”.

In 2007, Danida decided to phase out and redirect its support for development research from the mentioned research institutions and to broaden the use of the released funds through open competition. The phaseout was finalized five years later, and in this process, the ”Building Stronger Universities” initiative (BSU) was born as another kind of research capacity development framework. Since then, the BSU program has supported countries like Ghana, Tanzania, Uganda and Nepal.

”I was involved from the beginning of the BSU initiative with focus on areas like health, agriculture and governance. We aimed at strengthening research capacity at local universities by training PhD students and senior staff members locally, including courses in research management and methodology. We have seen good results and observed many graduates advancing to top positions in local administration or at universities, but we have also seen some taking up jobs which were not spot on in relation to their original education”.

Extending his network

During all these years, Peter Furu has worked as a consultant, researcher, and educator, involving himself and colleagues in projects in close partnership with institutions and individuals in low- and middle-income countries. ”Currently, I am involved in four research projects in Tanzania, Ghana, Togo, and Malawi. The thematic foci include topics such as climate change adaptation and gender, sustainable tourism, and epidemiology and control of vector-borne diseases. I resumed traveling after the Covid-19 pandemic late 2021 and, fortunately, local partners have been able to continue part of the work in the meantime, but overall, we have seen major challenges and delays in project implementation, as seen in most other development initiatives globally”.

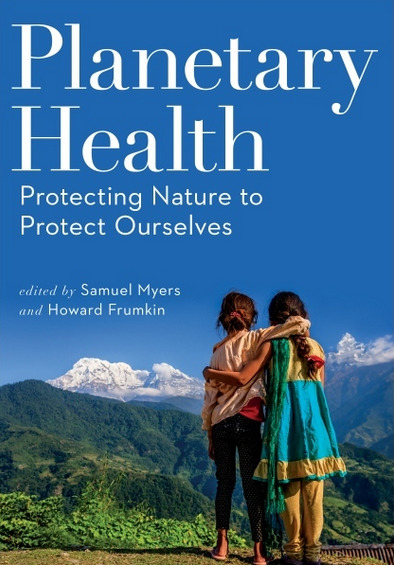

Peter Furu’s extended network consists, to a high degree, of younger colleagues in the South who have participated in earlier projects and received training and teaching from him and his colleagues at that time. When he embarks on new projects nowadays, it will often be in close collaboration with members of this network. He has also found new partners in the so-called “Planetary Health Alliance”, a global alliance with participating researchers from the South as well as the North that focuses on the health of the global civilization, focusing both on the state of the natural earth and human systems. The alliance has been developed with American funding from the Rockefeller Foundation and has its base at Harvard University, USA.

Livelihoods and health at risk

According to Peter Furu, “If the planet is not healthy, the livelihoods and health of communities may be challenged”.Therefore, during the last ten years, he has increasingly focused on the relationship between climate change and health in his teaching – and now also in his research. Since 2013, he has taught the course “Drivers of change in human health: Coping with population and environmental dynamics” at the University of Copenhagen as part of the Master of Science in Global Health program. “We prepare our students to make them be able to critically relate to development problems in a broader context in both low-, middle- and high-income countries. The learning therefore comprises traditional health topics as well as elements from agriculture, environment, water resources, and industry; sectors that may have activities and outputs that are important determinants of health”.