A large research project in close cooperation between researchers from Denmark and Burkina Faso has focused on what happens to epidemics when they emerge in unstable places with poor security, political unrest and mistrust towards the government.

Some epidemics begin among poor people in the countryside, then they spread to more privileged groups in the major cities and start crossing borders to other countries.

Other epidemics are flown in by airplanes, begin by infecting members of the urban elites – and only later spread to the countryside.

The fact that epidemics follow so different pathways makes it difficult to prepare properly for the next epidemic to arrive.

Preparing for the next epidemic was exactly the purpose of a major research project, initiated in 2018, before the covid-19 pandemic, by the medical anthropologist Helle Samuelsen from Copenhagen University, together with a group of colleagues from Denmark as well as Burkina Faso.

The project was named ”Emerging Epidemics” and received ten million Danish kroner from the DANIDA Research Facility (FFU). The goal was to prepare a kind of guideline for how to react to the very first signs of an epidemic in order to minimize its impact on a local society in low-income societies such as Burkina Faso.

”In a way, we were wearing blinders”, Helle Samuelsen explains. ”We were expecting something like the Ebola epidemic which haunted Western Africa a few years ago. If you use the experiences from Ebola, you expect the next epidemic to hit the poor people in the countryside first. We wanted to improve Burkina Faso’s preparedness against such kind of epidemics. But then Covid struck, and it hit the elite in the big cities first”.

”It makes a heck of a difference. It was a totally different scenario, and it called for a different communication strategy from the authorities. But having an epidemic playing out in front of us, it would be strange if we didn’t use our combined efforts to study that. So focus for the project was necessarily changed”.

It might be better named ”Epidemics in unstable places”.

”We have now been focusing on what happens to epidemics when they emerge in unstable places, i.e. places, where you have poor security, political unrest and mistrust towards the government already before the epidemic.”

Close partnership

Helle Samuelsen has studied health care and health care systems for many years in a number of countries around the world, including Burkina Faso, Pakistan and Tanzania.

Over the years, she has also been involved in designing new interdisciplinary courses at Copenhagen University in global health and global development.

She wrote her PhD-thesis, based on fieldwork in Burkina Faso in 1996 and 1997.

”I have kept contact with the same village and indeed the same family, whom I met when I arrived there as a PhD student for the first time. Since then, my research engagement has focused on West Africa and especially Burkina Faso”.

But after the first fieldwork in Burkina, she has established a close partnership with a group of colleagues at University of Ouagadougou and other local research institutions.

”Today, collaborative and interdisciplinary research is very common and the building up of long-term partnerships with colleagues in the Global South is extremely important. I couldn’t do the work I am doing without my strong network in the South. “It is really interesting and rewarding to work in equal partnerships with researchers in Burkina Faso.”

The South participants in the ”Emerging Epidemics”-project are both senior researchers from University of Ouagadougou and another research institution and three Burkinabe PhD-students in medicine, sociology and anthropology.

”Some of the senior researchers have their PhD degrees from France or Germany, but they have all conducted fieldwork in Burkina, and they live there today”.

From the Danish side, not only Helle Samuelsen is part of the team, also a group of epidemiologists from the School of Global Health at University of Copenhagen and a Danish PhD student are part of the research team.

Integrating local people

From the beginning of the Emerging Epidemics project, the goal had been to establish an ”ethically and culturally adjusted foresighting system” to help the health authorities in Burkina Faso to be better prepared for the next Ebola-type of epidemics that might emerge in their country.

”The basic idea for me and my Burkinabe colleagues was to integrate the local communities much earlier than before in fighting any future Ebola (or other epidemics) situation in Burkina Faso. In the villages, people know very early if something is wrong when new types of symptoms appear or when people start dying of unknown reasons. If this local knowledge could be gathered earlier, the health authorities would have more time to react to the threat”.

The idea was to create a kind of ”manual” for local people and authorities to follow in such a situation.

”Within medicine, you sometime have to use a so-called ’verbal autopsy system’. Instead of a physical autopsy, you conduct an interview with one of the surviving family members or maybe the local school teacher to get an idea what might have been the cause of death. Our idea was to use the same method, but not only when somebody had died. If you did it already when somebody was severely ill and reported the information, you might be able to prepare the health officials in the cities better to prevent and contain the epidemics”.

Because of the Covid-19, the scenario has changed and this type of manual may not be so relevant to develop within the current project,” but in relation to an epidemic similar to Ebola, I still think it could be a good idea. You shouldn’t throw out the idea. Maybe we will take it up later”.

What happened was, that the team of researchers suddenly had quite another emerging epidemic in front of them. A different phenomenon, which demanded a different kind of preparedness.

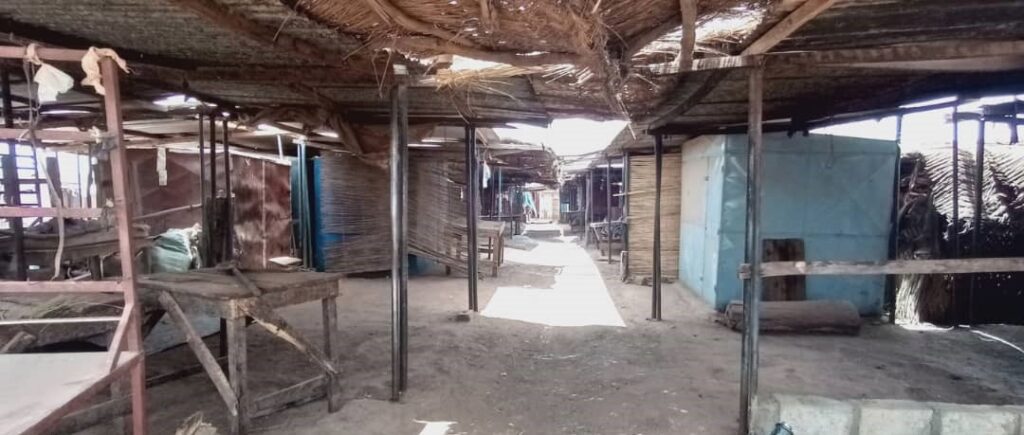

”We were able to observe”, Helle Samuelsen explains, ”that when the government declared a lockdown and tried to inform people about it, people didn’t believe it. They didn’t understand the necessity of a lockdown. Either because they thought that the government was ridiculous and corrupt, or because they simply had to continue to earn a living. When the local markets were closed for one month, many people didn’t have any income at all, and the government simply had to reopen the markets because of pressure and violent protests from desperate people”.

Local workshops

In the end, the project will result in four PhD-theses and around fifteen academic articles, most of them written in collaboration between researchers from South and North.

All these publications will be followed by policy briefs with recommendations to Burkina Faso’s government, its Ministry of Health and its district health services.

”We hope to be able to arrange a series of workshops with different stakeholders, in which we present our results and listen to their input and experiences. We hope to be able to hold these workshops in Ouagadougou before finishing the project, but because of the security situation, that might be difficult”.

”That would be a shame, as it is very important for us as well as Danida and FFU to communicate our research findings locally”.

As Helle Samuelsen sees it, the South participants have learned something about research methods, analysis, research leadership and for the junior scholars ”how to read and write a text academically”. They don’t have that many books in university libraries in the South.

”But we have learned just as much from our colleagues from the South. They are doing a large part of the fieldwork, and we couldn’t conduct a project like this without them. We are totally dependent on the good and trustful cooperation between us. It’s very difficult to make fieldwork in Burkina Faso at the moment. As a foreigner with a white face, I can travel to the capital city if I dare, but I cannot travel outside the city due to security issues. Most of the local PhD’s managed to conduct their fieldwork before the Covid-19 pandemic struck, but during the lockdown they couldn’t go from place to place either”.

Generally, Helle Samuelsen is worried about the limited focus on research into the Global South in Denmark. She understands the limited funding and the cuts in development assistance for the Global South as part of a general atmosphere in which a more national agenda gets increasing attention.

”It is strange that we show so little interest in the global world, measured in media attention, but also measured in resources”.

”It is very hard to find funding for research projects in areas far away, if you cannot argue with direct impact on some ongoing political debate in Denmark itself. I received public funding for my project, because Burkina Faso is one of the selected countries for Danish development assistance, but most countries in Africa are not on that list, and they are interesting as well. It is a shame”.

Actually, Burkina Faso has temporarily been removed from the list because of the precarious security situation, but we hope and expect it to be added again soon.

”The original idea of a research project into preparing for an Ebola-style epidemic is still extremely relevant for future study”, Helle Samuelsen reminds us.