In May 2022, Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS) published the policy brief ‘Decolonising Academic Collaboration: South-North Perspectives’. Earlier, researchers from Kenya, Ghana and Denmark, working together in three multi-year collaborative research programs, had met to discuss the inequality inherent in their collaborations. Professor Karuti Kanyinga, University of Nairobi, Kenya, is one of the participating researchers. He advises the Global South to respond to the unequal North-South academic partnerships instead of reacting; he also asks the North to change its attitude.

In June 2022, Professor Madhu Pai, Canada Research Chair in Epidemiology and Global Health, McGill University, Canada, and Associate Director of the McGill International TB Centre, tweeted his article ‘Passport And Visa Privileges In Global Health’ about the privilege researchers in the North have when they want to travel.

He wrote: “Right now, triple-vaccinated people in the Global North have declared the pandemic over and are rushing to travel everywhere with an ‘urgency of normal,’ and organizing more and more in-person meetings and courses. While they can travel at short notice and not worry about visas for entering a large number of countries, the reality is vastly different for people in the Global South.”

The tweet has since garnered more than 700 reposts and kept the conversation about the North-South relationships in research and academia alive. Movement, or lack thereof for academics in the global south, is one of the characteristics of the inequalities in the North-South academic collaboration. The pandemic also showed this power imbalance as the Global North—which accounts for under 15 per cent of the world’s population – secured half of all COVID-19 vaccine doses and denied visas to people not vaccinated. From the hallways of ivy league universities to the social media public sphere, academics are chronicling evidence of the existence of inequality in the North-South academic collaboration.

Open conversation, a start

In an interview with DDRN.dk, Karuti Kanyinga, Associate Research Professor, Institute for Development Studies (IDS), University of Nairobi, Kenya, wants more than to describe the impact of inequality. He apportions some responsibility on researchers and governments from the Global South. He calls them to have an open conversation about the entrenched geometry of power and authority and describes the current talks as “disconnected and vicious.”

He said: “Organisations that are Panafrican in nature must pick it up, put it on the table and let people talk about their experiences, to admit there is a need for collective voice and collective action, create a space for discussion almost immediately, and avoid disconnected talks.”

Prof Kanyinga said that he met young researchers at a conference early this year who declared that they would not cite the work of any academic working with an American organisation, regardless of the stellar quality of the work.

Refusing to cite academics’ work because of the country they got their funding from is irrational, Prof Kanyinga said. Still, the North’s “colonial attitude towards the Global South” and the academic environment in Africa create a fertile ground for that kind of resentment to thrive.

Continued dependency

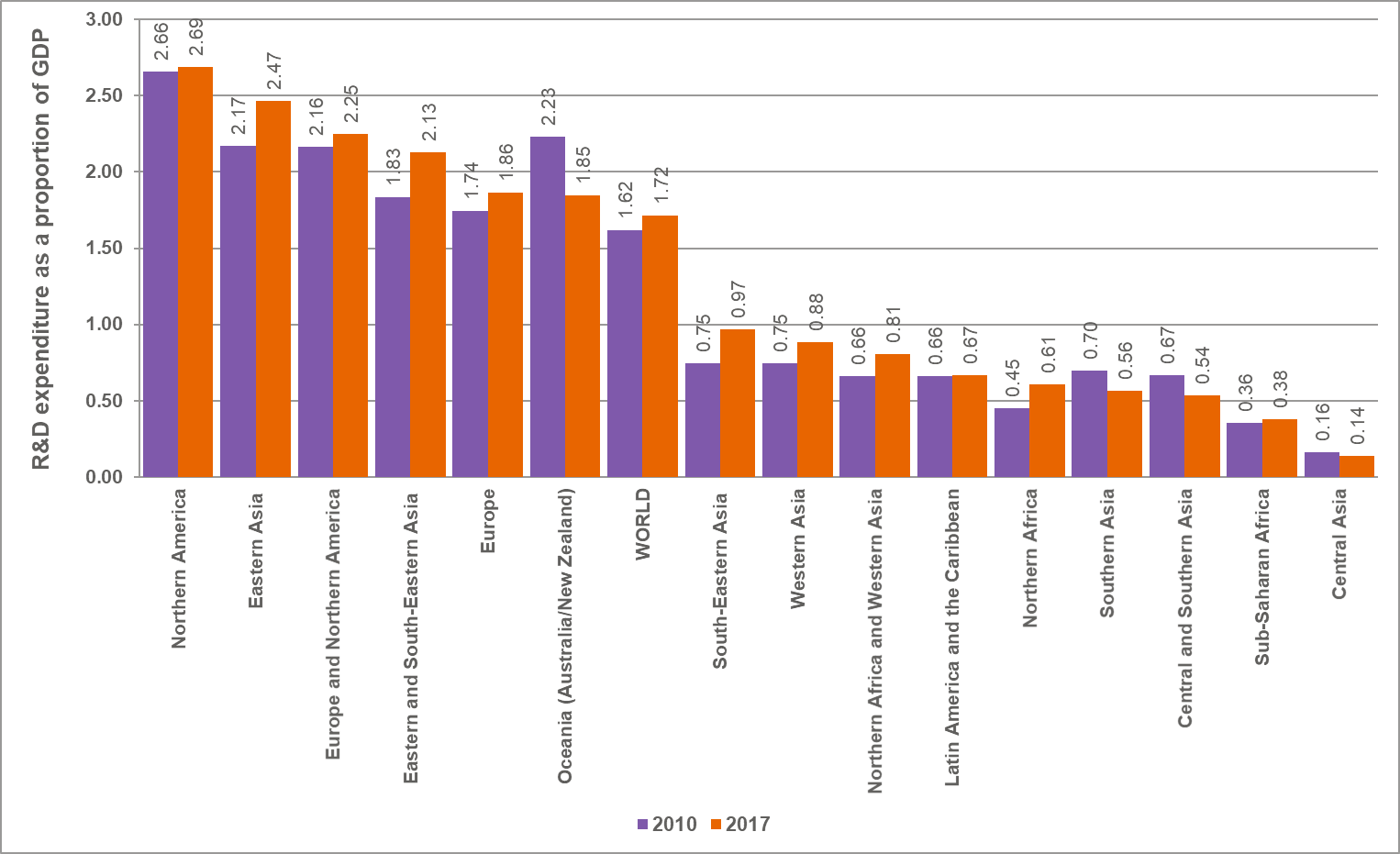

The African environment is where governments allocate little to no funding for research and higher education. Sub-Saharan Africa allocates 0.4 per cent of its GDP to research and development activities, according to 2020 UNESCO data. The dismal funding has led to continued dependency on the west for funding.

For example, nearly half of Kenya’s research funding comes from abroad. It is not better in Mozambique (78 per cent), Uganda (57 per cent), Tanzania (42 per cent) and Senegal (41 per cent).

Sometimes, the disdain for the North hurts young researchers in the Global South more than it would the older ones. Young researchers who get their PhDs from universities in the west come home to hostile colleagues who view them as privileged brats who took a shorter time to acquire the qualifications their local counterparts struggled to get.

The overreliance on donor funding leaves researchers in the Global South vulnerable to funding cuts. For example, the 2020 funding cuts in the UK slashed the aid budget to 0.5 per cent of gross national income, affecting some research in Africa and other countries in the Global South.

In an interview with DDRN.dk, George Nyabuga, Senior Lecturer, School of Journalism and Mass Communication, University of Nairobi, said that the shrinking funding for research in the Global North leaves little resources that researchers from both the North and the South have to compete for. As a result, the funding bodies will structure and value project outcomes and impacts according to their parameters.

“The North will also prioritise their researchers and universities and have little regard for what might be important to the global south,” Prof Nyabuga added.

There is evidence of this favouritism. For example, five researchers analysed a database comprising USD 1.51 trillion in research grants for climate change from 1990 to 2020. They found that Africa received less than 4 per cent of the funding to research topics relevant to the continent for climate change.

Reject “Saviourism”

Samuel Oji Oti, Senior Program Specialist, International Development Research Centre (IDRC), and Jabulani Ncayiyana, Senior Lecturer, School of Nursing and Public Health, College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal advise academics and practitioners in Global Health to reject ‘saviourism’. They ask them to refuse to “participate in partnerships that do not give equal opportunity and reward to partners from Lower and middle-income countries (LMICs). If it only were that black and white for academics in the Global South: they argue there is little room to take the moral high ground when senior researchers “need to bring in money to continue to pay the salaries of team members.”

Little domestic funding for African research and higher education has direct and perceived implications. Dr Nyabuga stated that the quality of research from underfunded research institutions remains questionable, making it difficult for the researchers to compete for the limited funding available. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that Africa produces less than 1% of global research output. Sub-Saharan Africa also records the lowest research output globally.

Yet, there is a lot that the North can learn from the Global South. Prof. Kanyinga said: “The Democratic Republic of Congo in Africa has an outstanding experience in responding to pandemics after years of dealing with Ebola; the North could have consulted their scientists on how to respond to COVID-19, another viral disease.”

Eurocentric canon of knowledge

Even in areas of excellence, such as response to pandemics, the Global South also participates in the disregard of its excellence, constantly working towards achieving “international standards”. Dr Kumari Beck, Associate Professor, Faculty of Education, Simon Fraser University, Canada, said academics in the South and North should acknowledge colonialism in their backyards. She said that colonialism is at the centre of “academic imperialism”. Dr Beck explained that academics in the Global South work towards the international ideal because of their belief that “the West is the best.” That belief, Prof. Achille Mbembe University of Witwatersrand, South Africa, said, is a “Eurocentric canon that attributes truth only to the Western way of knowledge production.”

“It is a canon that tries to portray colonialism as a normal form of social relations between human beings rather than a system of exploitation and oppression,” Prof. Mbembe wrote.

Dr Beck calls for self-awareness of the influence of colonialism in higher education for academics in the North and South. When they are aware, they will know how colonialism affects academics’ view of the research questions, the set of assumptions about how the world is from the colonial lenses and how people can only access that world through particular methods. With this awareness, researchers in the Global South will discuss roles and responsibilities at the beginning of the research. In return, the North should come with the intent to listen and learn, not impose their ideologies, and direct.

Academics in the Global South see the unequal North-South academic collaborations as a legacy of colonialism, especially in areas such as Global Health. Making and Unmaking Public Health in Africa Ethnographic and Historical Perspectives, edited by Ruth J. Prince and Rebecca Marsland, talks about how the church and the colonial authorities married educational, political and healing systems, making them ‘intimately tied to a repressive, coercive and violent system of power and knowledge’. The education that the missionaries offered the Global South was meant to prepare the students to be efficient workers in factories, school or hospitals for the benefit of European economic investments. The colonialists bastardised indigenous education systems with false narratives about western moral and intellectual superiority. This cultivated the “saviour mentality” that justified, rationalised the colonial presence in the Global South. Years after the end of colonialism, the perception of the superiority of western knowledge persists, further commodifying knowledge and its production, as the Global South still looks to the North for funding.

The Global South has expressed discontent and requested their colleagues and funders from the Global North for mutuality. Seeing no more than declarations, researchers in the Global South are devising strategies they can apply to confront the inequality. Dr Kumari Beck, from the Simon Fraser University, asks Global South academics to acknowledge how they have internalised the colonially influenced mindset that pushes them to work towards adopting “international standards” to get the funding from the North.

Prof. Karuti Kanyinga, University of Nairobi, has monitored the impact of inequality in North-South academic collaborations. He suggests that the Global South acknowledges the crisis that makes it vulnerable to exploitation. Prof. Kanyinga encourages scientists to agitate for funding for research and development activities from their governments, and not be overly dependent on the North.

Verah Okeyo is a Nairobi-based journalist and communications specialist who tweets at @iamverahokeyo.